By Ariella Cohen, The Lens staff writer |

In January 2002, a mound of powdery chemical catalyst used to make gasoline collapsed on a worker doing routine cleanup at the Marathon Ashland Petroleum refinery in Garyville, La.

Within minutes, the contract employee, from Colfax, was completely engulfed in the toxic chemical and struggling to get free. Before help arrived, the face seal on the man’s helmet broke, allowing fresh air to hit the catalyst and ignite. “Employee #1 was killed as a result of chemical burns,” reads the Occupational Safety and Health Administration report on the death, which was tagged a “housekeeping” issue. The incident report ends with no violations listed and no penalties imposed.

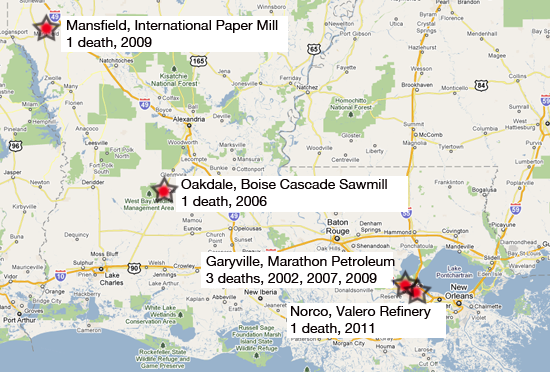

Marathon, which would experience another fatal accident in 2007 and again in 2009, has been considered by the federal government to be one of the country’s safest places to work for nearly two decades, one of 2,434 across the country certified by OSHA as a Voluntary Protection Program site.

That status makes the refinery part of an elite group of businesses that serve as ambassadors between industry and the agency’s safety inspectors. In exchange for professing a commitment to safety and carrying that message to private-sector peers, program members get a three-to-five-year exemption from routine OSHA inspections and a friendlier relationship with the feds, not to mention bragging rights useful to the public relations department. Created in 1982 as part of the Reagan Administration’s effort to shrink the federal bureaucracy, the program was an experiment in industry self-policing.

After two decades of slow growth under Reagan and his White House successors, George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, the self-enforcement program took off during George W. Bush’s eight years in Washington.

One of the few OSHA initiatives spared cuts during the Bush administration, the program was promoted as a way to encourage employers to voluntarily comply with safety standards at a time when regulations and enforcement efforts were being steadily rolled back. Under Bush, the number of workplaces blessed with the OSHA model-workplace certification tripled nationally, despite warnings from government auditors that such ambitious expansion could threaten the program’s integrity.

Today, the program continues to grow and Congress is considering legislation, co-sponsored by U.S. Sen. Mary Landrieu, D-La., that aims to expand it even further. In addition to codifying the program and expanding access to it, the legislation would prevent OSHA from imposing the user fee it proposed last year to cover increased inspections of participating workplaces. Current rules call for inspections only in the event of a fatality or if a complaint is filed.

If the proposed legislation becomes law, Louisiana – which already has more self-regulated sites than any state other than Texas, Pennsylvania and Ohio — is expected to see a jump in participation.

“Louisiana has one of the largest number of VPP sites in the U.S., and from my experience working with companies in the state, those companies that are in have a true commitment to workplace safety and health,” said Davis Layne, executive director of the Voluntary Protection Program Association, a nonprofit trade organization. “Many other companies are now seeing that value and trying to get involved.”

The commitment to safety may be sincere, but evidence that the program is actually achieving its goals is hard to come by. The deaths at Marathon are not the only fatalities at these so-called model workplaces. Since 2000, at least 74 workers have died at certified sites and agency investigators found serious safety violations in at least 47 cases, according to records examined by The Lens in collaboration with Center for Public Integrity’s iWatch News. In Louisiana, there have been six deaths since 2000, including the three at Marathon in Garyville and two at other facilities that were linked to serious violations of their safety code. None of the Louisiana deaths resulted in companies losing model workplace status.

Indeed, the disconnect between the Voluntary Protection Program’s goals and its results is especially stark in Louisiana, where a large petrochemical industry puts workers in daily contact with life-threatening risks that are not measured by the program. The big problem, program critics contend, is that the potentially catastrophic risks inherent in refinery operations aren’t meaningfully reflected in the personal-injury data that is the program’s primary metric.

“In a refinery, not fixing a pipe or repairing a machine can lead to a major explosion and a slip-and-fall rate is not going to help you know if that repair or maintenance was done,” said Celeste Monforton, a former OSHA policy analyst who now is a lecturer in environmental and occupational health at George Washington University.

The agency’s records lend validity to Monforton’s concern. Petroleum refining facilities account for only about 7 percent of OSHA’s model workplaces in Louisiana – six out of 107 sites. Yet four of the last decade’s six fatalities – 67 percent— occurred in those petrochemical facilities. Nationally, at least 11 of the 74 site- recorded fatalities between 2000 and 2010 — 15 percent — happened at refineries, all of them in Louisiana or Texas, OSHA records show. Additionally, these facilities increasingly depend on contract workers – like the man who died of chemical burns at Marathon’s Garyville plant — whose injuries or days lost are simply omitted from the personal injury rate average that serves as the program’s primary metric for measuring workplace safety. This means that refineries could have a higher rate of on-site injury than allowed by program standards, yet still be certified because a sector of its workforce isn’t factored into the equation.

In March, a contract worker at Valero Energy’s facility in Norco, a certified program participant, fell from a ladder to his death. A malfunction in the plant had exposed the worker, Victor Rodriguez, 30, to dangerous levels of the toxic gas hydrogen sulfide in the minutes before his fall.

His family is now suing Valero and the contracting company that employed him for wrongful death.

“What happened was a breakdown in the process safety management,” Byron Buchanan, a lawyer for the deceased contractor’s family, said.

But while the Houston lawyer contends that the fatal accident was preventable, and possibly indicative of a larger weakness in the refinery’s process management system, it’s unlikely to affect Valero’s status as a model for workplace safety or cost it money in fines, analysis of OSHA inspection data shows. Among the fatalities that previously occurred at federally certified sites in Louisiana, three of the five complete accident investigations — 60 percent of the total and all of them at Marathon — resulted in no penalties.

While refineries avoided fines, wood and paper companies weren’t so lucky. After a worker was killed at the International Paper mill in Mansfield, OSHA fined the company $10,000 for two separate violations. No summary of the accident was included in OSHA’s investigation but records show the violations were for failing to maintain proper guard rails and other safety mechanisms. The 2009 fines remain outstanding, though the company told OSHA it had fixed the problems in 2010.

In Oakdale, a Boise Cascade sawmill was assessed $4,410 after an employee was fatally struck by a tractor-trailer while walking to his workstation. “The intersection of the drive aisle was not marked or controlled by signals or stop signs,” an OSHA inspector noted in the accident investigation summary. The lack of traffic signage led to an initial fine of $6,300.The agency later settled with the company for $4,410 in penalties.

OSHA did not respond to a request for information about the mill deaths. It was not, however, the agency’s first time fielding questions about a worker death at a safety-certified International Paper mill.

In 2008, a catastrophic boiler explosion at a mill in Vicksburg, Miss., killed one worker and injured another 22, leaving at least three in medically-induced comas for months while doctors treated serious burns. In a subsequent investigation OSHA discovered that the Tennessee-based company had ignored an internal memo outlining recommendations that, if followed, would have prevented the explosion or minimized risk to workers, according to records examined by the Center for Public Integrity’s iWatch News. OSHA, in its investigation, alleged violations of safety standards that program members are expected to exceed, yet the company did not lose certification.

Texas refineries have been less successful than their Louisiana counterparts in avoiding fines following fatalities, OSHA records show, perhaps in part because the deaths at program-certified refineries in Texas have been associated with more catastrophic failures of systems and machinery. In total, 54 percent of fatality investigations at Texas refineries — four out of seven — resulted in fines compared to zero in Louisiana.

What the two states have in common, however, is that none of the fatalities resulted in an establishment losing OSHA certification as a model for safety. After a worker was killed and another seriously injured by a preventable boiler explosion at a Valero refinery in Texas City, for instance, OSHA issued the Voluntary Protection Program participant a citation. The 2009 blast had thrown one of the workers under a stainless steel tank, causing “fatal blunt force trauma,” the accident report reads. Valero hasn’t paid its $4,500 penalty, or suffered a fall from grace as part of the model-workplace program.

At Marathon in Garyville, another worker died after mistakenly driving his pickup into a wastewater retention pond on the refinery’s grounds. By the time co-workers answered his radio call for help, the technician’s Ford F-150 was completely submerged. “Employee #1 was found at approximately 3:00 a.m. on September 1, 2007, drowned in the pond,” reads the OSHA report. Again, no violations were found and no fines imposed on the refinery, which was certified as a model workplace in 1994. In the report’s concluding lines, an inspector notes that there are no lights in the area. No penalties were paid and the site remains part of OSHA’s model program.

Ignoring a slap on the wrist, losing a life

Nationally, about 70 percent of sites where a worker has died since 2000 remain in the program today. Typically, a site is removed from the program only after repeated incidents demonstrate chronic mismanagement. At a certified Weyerhaeuser Co. paper plant in Oklahoma, for instance, a worker was crushed to death in a paper machine two years before the site was reapproved for model workplace status. Less than two months after the site was recertified, another worker was crushed to death in a paper machine and OSHA found the same violations that had been cited in the first death, documents obtained by the Center for Public Integrity show. Only then did OSHA remove the site from the program.

That reluctance to decertify doesn’t surprise personal injury lawyer Buchanan. After years of representing Texas oil industry workers, he says he has seen no significant difference between certified and uncertified workplaces.

“My experience in Texas is that when a site is (allowed into the program), safety conditions are not vastly improved,” he said. “The certification could be tied to under-reporting more than anything else.”

OSHA did not answer questions from The Lens about the model-workplace program’s implementation in Louisiana, or respond to repeated requests for an interview with the program’s regional supervisor. The agency also failed to turn over personal injury data that must be made public upon request under the Freedom of Information Act. “People are stretched thin,” spokesman Jesse Lawder said when a reporter asked why questions still had not been answered a month after they were submitted. A spokeswoman for the agency’s regional office, Elizabeth Todd, referred all inquiries to Washington.

Landrieu, who counts Marathon Oil and other Voluntary Protection Program participants among her biggest financial backers, declined multiple requests for an interview to discuss the program or the pending legislation codifying the program that she helped write.

In an interview with iWatch News, OSHA Deputy Assistant Secretary Jordan Barab defended the program. A death leading to the discovery of serious violations is “certainly a strong indication that you’ve got a serious problem,” he said. But overall the program is “very useful as a model to all employers of what can be achieved,” he added.

A partnership between industry and its regulator

OSHA and program advocates like Landrieu sell self-regulation of workplace safety as a way for government and industry to work together and ultimately, save both sides money. In 2007, a typical year, the agency estimated that the program had saved taxpayers more than $59 million and participating companies more than $300 million.

That corporations would wind up assuming more of the regulatory burden and yet actually save money might seem counter-intuitive. Bill Day, a spokesman for Valero Energy Corporation explains it this way: “The benefits are priceless. Not only do you know that your employees are safer, but from a more dollars-and-cents perspective, safer also means more efficient, fewer breakdowns, less worker turnover and a better relationship with OSHA.” Valero, which operates 11 refineries with model-workplace status, including one at Norco, is pursuing certification of its remaining seven in North America. Day declined to comment on Victor Rodriguez or the incident at Norco that took his life.

To join the model-workplace program, companies must submit to an on-site evaluation. Unlike the usual OSHA visit where inspectors can issue citations, however, evaluators — often including employees of companies in the program — issue “90-day items,” a list of hazards to correct within 90 days. Once a site receives certification, OSHA allows it to police itself. Inspections happen once every three to five years unless triggered by a serious accident, formal complaint or a referral of a potential hazard. Moreover, the status exempts sites, from any industry-specific safety programs that OSHA uses to crack down on workplace hazards — regardless of perceived risk.

Whether or not fatal accidents should be tolerated at workplaces held up as models for safety is a question some in Washington are asking. A Government Accountability Office audit of the Voluntary Protection Program in 2009 found that “sites that no longer met the definition of exemplary workplace” remained in the program, and that “OSHA’s lack of internal controls are not sufficient” to stop that kind of adulteration of the program from happening on a routine basis.

More broadly, auditors determined that OSHA had never developed goals or measures to assess the program’s performance, making any effort to evaluate it “inadequate.” In final recommendations that have not been implemented, the accountability office suggested OSHA tighten internal controls and collect more data so that potential catastrophes can be predicted and prevented. Like Monforton, the former OSHA employee now teaching at George Washington University, auditors say that personal injury data isn’t a sufficient barometer of safety at a high-stakes workplace like a refinery, where a simple procedural mistake has the potential to end lives.

“They don’t track what almost happened, just what does,” GAO investigator Revae Moran told The Lens. The lack of documentation can make it “difficult to take preventative action,” and hard to prove when an incident is symptomatic of a larger pattern of sustained or willful negligence, she said.

That lesson had been taught before, but evidently not learned. On March 23, 2005, a jet fuel manufacturing unit at a BP refinery in Texas City went up in flames, killing 15 people and injuring more than 170. A subsequent investigation found that as part of a cost-cutting drive in the years before the deadly explosion, BP management had placed temporary trailers next to the volatile fuel-making unit and made personnel changes that workers felt compromised their job safety.

For lack of stringent reporting requirements on the refinery’s safety processes, the compound effect of these changes was not realized until it was too late, industry post-mortems revealed. An investigation of the explosion by an independent blue-ribbon panel headed by Texas lawyer James Baker, a former cabinet member in the administrations of Reagan and both Bushes, found that better reporting on refinery conditions would have reduced risk.

Most relevant to the Voluntary Protection Program was the finding that relying on the personal injury rates that qualify companies for the OSHA program contributed to the cascading failures that ignited the Texas City refinery. “BP mistakenly interpreted improving personal injury rates as an indication of acceptable process safety performance,” the Baker panel report stated, adding that “reliance on this data combined with an inadequate process safety understanding created a false sense of confidence that BP was properly addressing safety risks.”

OSHA responded to the Baker panel’s findings with a new program of inspections targeting refineries — the National Emphasis Program. A program fact sheet distributed in 2007 drove home the need to target refineries. The total number of potentially hazardous chemical releases between 1992 and 2007 at petroleum refining facilities surpassed the combined totals of the next three highest industries: chemical manufacturing, organic chemical manufacturing and explosives manufacturing.

Yet even with this stark evidence of heightened risk, OSHA exempted Voluntary Protection Program sites from the National Emphasis Program. Moreover, for lack of sufficient staff and budgeting, OSHA’s regional offices have failed to inspect eligible sites. In Louisiana, for instance, where hundreds of petroleum manufacturing businesses are subject to inspection through the program, OSHA has done only 10 planned inspections since the its launch four years ago. The inspections, though rare, were fruitful, resulting in 173 citations, many of them for violations classified as serious by OSHA, agency records show.

The exemption of model-workplace sites from subsequent inspections makes it impossible to fully compare their safety records with the performance of inspected sites. But the probe that followed the 2002 death from chemical burns at Marathon’s Garyville site revealed a procedural safety failure of precisely the kind targeted by the National Emphasis Program, from which the facility was exempt.

Inspections of Marathon refineries that aren’t part of the exempting program have turned up repeated allegations from OSHA that the company is violating safety regulations and in some cases, demonstrating “plain indifference” to them. A 2007 inspection of an Ohio refinery ended with citations for 45 violations, 42 of them serious and 2 classified as “willful” totaling $321,500 in fines, OSHA records show.

Marathon declined to answer inquiries for this article. Company spokesman Robert Calmus told iWatch News that he would not discuss specific incidents, but said the company is “a strong supporter of the VPP program and is proud to have many of its facilities VPP certified.”

Barab, the OSHA assistant director, has said that fatalities at exempt sites have caused the agency to consider reinstating industry-specific inspections for refineries that enjoy model-workplace status. “We have had some fatalities in VPP refineries, so that’s something we are still trying to figure out,” Barab said in an interview with iWatch News. “Our general plan is to inspect at least a few VPP refineries and decide for ourselves whether we really need to continue the exemption.” He said that the agency hasn’t begun those inspections because it is already stretched thin doing inspections of sites already on its priority list. “We haven’t really been able to pull out of that yet,” he said.

Though the legislation to codify the program that is now moving through Congress mandates more internal controls and documentation at participating workplaces, it reinstates the exemption and doesn’t offer any specific requirements for new controls or reporting.

And if the bill passes, said Layne, of the trade association for self-regulated workplaces, the exemption will be only harder to lift. “If you are a refinery and you are in the VPP you already get more rigorous scrutiny than if you are not in the program,” he said. “The advantage of having it placed into law will then make it funded through normal appropriations.”

Asking the driver to police his ride home

Norco refinery electrician Wilton Ledet has seen co-workers burned by boiling chemical catalysts, frostbitten by propane and cut by tools that don’t have required guards. He has helped co-workers off the shop floor after falls from 20-foot ladders. “I’m lucky none of my guys have died,” said the 20-year veteran of the Shell-Motiva plant, and president of the United Steel Workers Local 750. After years of advocating for better worker conditions, Ledet is an ardent opponent of the Voluntary Protection Program.

A central tenet of the self-regulatory program is cooperation between management and the rank-and-file workforce – all applications require sign-off by an employee representative, or a union official if a site is organized. In recent years, the refinery’s management has approached Local 750 about pursuing certification in the OSHA program, but union membership has voted against it, Ledet said. He likens the program to asking drivers to police their commutes home. “My thing is, am I going to speed home from work, get home and then call the police and say, ‘Oh, I sped home?’ ” Ledet said.

“If a company wants to be in a program that bad, there is a reason why they want it. That reason is not my safety,” he said.

Shell’s Norco refinery did not respond to multiple requests for an interview, but Layne, the trade group rep, says that Ledet is underestimating the program’s value. “It forces management and workforce to come together, reduces employee turnover, reduces management friction, and reduces injuries,” he said.

Layne also disputes the notion that participating refineries receive less scrutiny than non-certified peers because they are not subject to regular OSHA inspections. To make this point, he recalls an explosion at a Tesoro refinery in Washington State that killed four people just one year after OSHA inspectors were there. The inspection had cited Tesoro for 17 health and safety violations that, at the time of the explosion, were being challenged rather than repaired. “Just because they go in and make an inspection, there is no guarantee that anything is resolved,” Layne said.

With an annual budget that is a fraction of other federal agencies and constantly under attack by anti-regulatory interests, OSHA has long struggled to carry out its broad mandate. But while self-regulation has been held up as a solution, Monforton says that well-intentioned initiatives like the Voluntary Protection Program could in fact be costing the public more than they save.

“The principles espoused by VPP are good and the goals are laudable, but I have not been convinced by any data that the government investment is worth it,” she said. “If you get to wave the flag of government-certified safety, you should not have situations where workers are drowning in ponds because there are no lights. We are rewarding companies for non-exemplary behavior and then paying to oversee that reward.”

In Louisiana’s ConocoPhillips Refinery in Belle Chasse, workers recently teamed up with management to get OSHA certification as a model workplace. Anthony Corso, chairman of the refinery’s USW local, supported the move because he saw it as the only way to upgrade the long-neglected facility. “They were dragging their feet on a lot of repairs we’d been asking for but once they wanted their VPP status they picked up,” Corso said. “They wanted to get the site back up to speed.”

Corso estimates that ConocoPhillips, which earned $3 billion in profits in the first quarter of 2011, spent about $1 million to bring the Belle Chasse plant, its second largest in the U.S., up to code. The improvements ranged from basic repairs of guardrails on equipment and cages on ladders to larger pipe fixes, Corso said. The veteran refinery worker worries whether the investment will continue now that the certification is complete.

“We heard from other folks at other refineries that after they get the certification, they stop listening, but right now, we are pleased,” Corso said. “A year and half from now, we may be saying something else.”