New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu says safety, not money, is behind a major expansion of traffic enforcement cameras in the city.

But his administration has produced no evidence the cameras reduce wrecks, injuries or deaths on New Orleans streets.

It does have data on how many tickets have been issued and how much money they brought in.

The city is adding 45 stationary cameras and 10 mobile ones to catch drivers speeding or driving dangerously in school zones. The new cameras are expected to bring in about $5 million a year after the vendor takes a $3 million cut.

After several public records requests, the city provided just one study that touched on safety. It doesn’t appear to support the city’s case, instead showing that school zones without traffic cameras were, on average, safer than those with them.

American Traffic Solutions, the Arizona company that runs the cameras, is required to provide the city with a detailed traffic and safety study on any proposed camera location. That apparently hasn’t happened.

The city couldn’t produce any studies performed by the company since 2007, when the two signed their first contract.

The lack of data on traffic safety runs counter to best practices on how to use cameras to enforce driving laws.

Experts recommend local governments study traffic volume, speeding and crashes before cameras are installed so they can pick the best sites. After they’re set up, experts say those studies should be repeated to measure the cameras’ effectiveness.

“We do not behave well behind the wheel, and as a consequence, we threaten each other’s lives. … You don’t need a study to see that in New Orleans.”—Mayor Mitch Landrieu

A guide published by the Federal Highway Administration says the public should be made aware that the cameras are “used to improve safety, not to generate revenue or impose ‘big brother’ surveillance.”

City officials have said the cameras are changing how people drive.

When WWL-TV asked in January if there has been a citywide reduction in crashes since the program started, a city spokesperson cited the number of tickets that have been issued and a survey in which people said they had changed how they drive after being ticketed.

“We do not behave well behind the wheel, and as a consequence, we threaten each other’s lives,” Landrieu told NOLA.com’s editorial board in October. “You don’t need a study to see that in New Orleans.”

66Ticket cameras in New Orleans last year55More are being added this year, including 10 mobile units

Cameras bring in millions in fines

The city’s camera program started in 2008. Last year, there were 66 cameras in 42 locations. Some target drivers who run red lights and speed through intersections. Others watch for speeding in school zones. A few more enforce speed limits outside school zones.

State law requires signs telling drivers where cameras are in use.

When someone speeds or drives through a red light where a camera is mounted, the system captures a photo of the car’s license plate and a video of what happened. A city police officer reviews the video. If he decides there was a violation, the registered owner of the car gets a ticket in the mail.

Fines range from $75 to $235. Tickets don’t count against your official driving record.

The city issued about 252,000 camera tickets last year, compared to about 230,000 in 2015.

$16 millionEstimated revenue from traffic cameras in 2016$8 millionMore expected each year from the new cameras

They brought in about $16.1 million in 2015, more than parking tickets and several times more than tickets at traffic stops. City officials estimate collections were about the same last year.

About 30 percent of the fines goes to American Traffic Solutions, which administers more than 3,000 cameras nationwide.

Do traffic cameras make New Orleans roads safer?

In general, wrecks are increasing in New Orleans, according to the Highway Safety Research Group at LSU. The number of crashes on city-controlled roads has increased every year since 2011. So has the number of wrecks with serious injuries.

What about wrecks at camera locations? We don’t know.

Some states require local governments to report how many wrecks occur in automated enforcement zones. Louisiana is not among them.

The Lens asked the city for studies showing the effectiveness of the cameras — specifically, records related to car wrecks.

“Reduced speeding decreases the likelihood of crashes and increases public safety.”—City spokeswoman Erin Burns

The city provided summaries of studies by a national traffic safety research group, a local survey of people who had gotten camera tickets, and two reports on how many citations had been issued in New Orleans over several years.

City spokeswoman Erin Burns said the documents “show a reduction in speeding violations as a result of the traffic safety camera program. Reduced speeding decreases the likelihood of crashes and increases public safety.”

We found a few studies showing a relationship between traffic violations and crashes. However, the author of a report on red-light cameras in Lafayette wrote that while “the number of violations may be an indicator of safety, the true safety measure involves the number of crashes and their severity.”

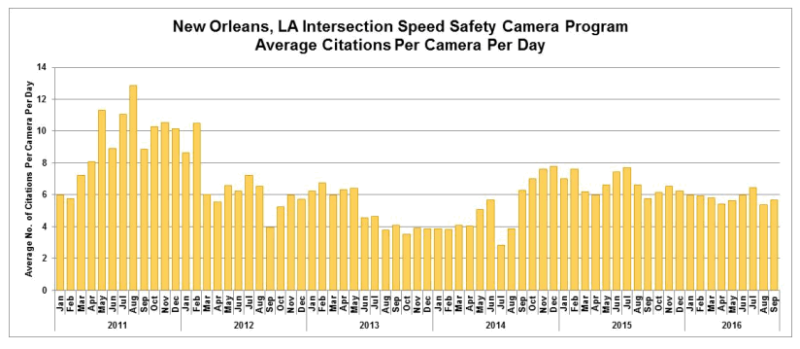

A report written by American Traffic Solutions last fall does show a drop in the average daily number of speeding tickets at intersections with cameras. But the big drop occurred in early 2012, when the city raised the threshold for issuing tickets.

Tickets dropped further in 2013, but they rose again. By last fall, the daily average per camera was about what it was in early 2012.

Other types of tickets have not dropped. Red-light violations went from a daily average of fewer than 10 to about 15. School-zone cameras don’t show any obvious trend. (The city doesn’t issue speeding tickets when the lights aren’t working, which has been a problem.)

Another report compared violations from when cameras were installed to June 2011. It showed a drop, but it didn’t compare the same months. For instance, the report showed a decrease in speeding tickets in school zones from the spring and fall of 2009, when schools were in session, to June 2011, when most weren’t.

After we asked a couple more times, the city provided a report about car wrecks. It focused on 134 school zones, including 19 with cameras.

The city used crash data between 2011 and 2015 to create a “safety index” for each school zone. The index was based on the number and frequency of nearby crashes and crash-related injuries and deaths. The higher the score, the more dangerous it was.

The 19 school zones with cameras had a higher average score — meaning they were more dangerous — than the 115 school zones without them.

“The questions one would really ask the decisionmakers is if they have done a safety study to make sure the objective of the cameras is for safety, not to generate funds.”—Helmut Schneider, Louisiana Transportation Research Center at LSU

We asked the city for the underlying data, but the crash figures came from the state and the city agreed to keep them confidential. We requested them from the state Department of Transportation and Development in early February; we haven’t gotten anything.

For the 19 locations with cameras, the study didn’t compare crashes before and after they were installed — so it’s impossible to say what effect they’ve had.

That’s what the director of the Louisiana Transportation Research Center at LSU said cities should do. First they should study traffic and accident patterns at each proposed location to see if the cameras are necessary. They should do it again after cameras are up, to see if they’re effective.

“The questions one would really ask the decisionmakers is if they have done a safety study to make sure the objective of the cameras is for safety, not to generate funds,” said Helmut Schneider, the director.

“From a safety perspective, yes, the cameras can increase safety, but you should really do that for every intersection.”

A city spokeswoman declined our requests to interview city officials about their studies and our findings.

The city’s contract with American Traffic Solutions requires the company to do precisely what Schneider described. The company is required to study “traffic characteristics” at every proposed camera site, including traffic volume, tickets issued and crash frequency.

The Lens asked the city for those studies dating back to 2007. The city said it didn’t have any.

The company couldn’t provide them, either.

After repeated requests, Marc Ehrhardt, who works as a local spokesman for the company, gave The Lens results of three mobile traffic camera tests in 2015. They show the number of violations at each site but don’t address crashes.

He also provided a summary of studies the company performed at the new camera locations. That spreadsheet was created to respond to our inquiries, and it hadn’t been given to the city.

It summarizes the company’s analysis of which of the proposed sites were suited for cameras, accounting for things like traffic volume, speed limits and traffic signal timing.

We didn’t see anything in the spreadsheet about wrecks — or anything that showed these cameras were needed in the first place. We asked Ehrhardt about this and told him the contract requires the company to look at crashes. He didn’t respond.

Nationally, mixed reviews of traffic cameras

Outside New Orleans, there’s plenty of research about traffic cameras and safety. Trouble is, it’s hard to draw conclusions from them.

Many studies have shown traffic cameras make roads safer.

In 2007 and 2008, Schneider, the Transportation Research Center director, studied six intersections in Lafayette with red-light cameras, starting a year before they were installed and ending a year later.

He found that crashes decreased by 13 percent. “T-bone” wrecks — the type often caused by a driver running a red light — decreased by a third. Rear-end crashes remained about the same.

However, “in some locations, it increased the rear-end collisions,” which aren’t as severe, Schneider said.

That’s what some studies, including one conducted in 2005 by the Federal Highway Administration, have found: Red-light cameras often reduce T-bone wrecks but increase rear-end crashes. That’s probably caused by drivers slamming on the brakes to avoid a ticket.

One of the biggest proponents of traffic cameras is the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, which is funded by insurance companies.

It studied fatal wrecks caused by drivers who ran red lights in 14 cities, starting in the mid-1990s before cameras were in use and ending a decade later when they were. The study found accidents in those cities decreased by 24 percent, compared to a drop of 14 percent in 48 cities without red-light cameras.

In another study in Maryland, the institute showed cameras led to lower rates of speeding.

But the more studies we read, the murkier it got.

The Florida transportation department tracks camera programs around the state. A December survey of about 150 intersections with red-light cameras showed that accidents increased by about 10 percent compared to the same intersections before they had cameras. Rear-end crashes went up 11 percent; T-bones rose about 7 percent.

13% dropIn crashes at six Lafayette intersections after cameras were installed10% riseIn crashes at about 150 Florida intersections after cameras were installed

A study in Phoenix released in 2013 concluded speed cameras had no statistical effect on the number of crashes.

And the Chicago Tribune found that cameras increased the number of injury-causing accidents at intersections where there had been few crashes.

Schneider said that even the Lafayette study had mixed results after weighing the cost of ticket fines against the cost of wrecks, such as repairs, emergency response and healthcare. At three of the six intersections studied, estimated ticket revenues exceeded the estimated savings from fewer crashes.

“One would like to have the reduction in those crash costs to be larger than the revenue from the camera tickets,” he said. “If the revenue is more than the crash costs, then the citizens are paying more than they’re saving.”

“One wouldn’t want cameras to just be a revenue generator.”