Ever since the extent of the Deepwater Horizon spill became obvious, coastal advocates have said the disaster had a silver lining: The fines BP eventually would pay might solve the giant funding hole in the state’s $50 billion Master Plan for the Coast. That’s the last, best hope to prevent the crumbling, sinking bottom third of the state from being swallowed by the rising Gulf of Mexico by the end of the century.

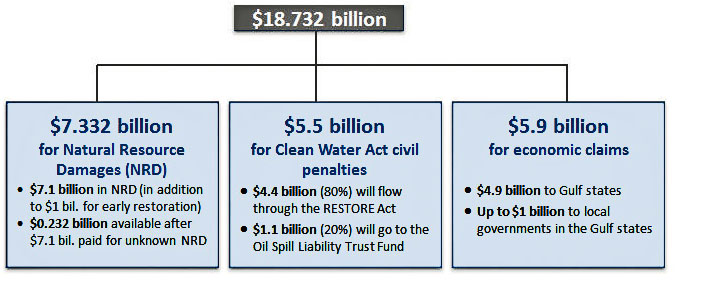

But a review of Louisiana’s share of the record $18.7 billion, multi-state settlement shows that while the windfalls give the plan breathing room for a decade or more, far more will be needed.

“It’s still a drop in the bucket compared to the overall needs for the plan,” said Chris Dalbom, of the Tulane Institute on Water Resources Law and Policy. “The best-case scenario is this is all kind of seed money to get Master Plan projects going in earnest.”

The 2012 edition of the Master Plan calls for spending between $700 million and $1.3 billion per year in 2010 dollars to achieve its goals by 2060. When Tulane adjusted those figures for inflation, it found the ultimate cost of the program would be $92.3 billion, indicating the annual spending would need to be closer to $1.5 billion. But the plan currently has a recurring funding stream of just $280 million.

The settlement, which still must be approved by a federal judge, shows the state receiving about $500 million a year for 16 years. That would increase annual income for the plan to almost $800 million – but only until 2032.

Hopes that the Deepwater Horizon would be a larger economic boon to the Master Plan always rested on BP being held to maximum penalties for fines under the Clean Water Act and restitution required under the Natural Resources Damage Assessment. Some of those estimates ranged as high as $22 billion for Louisiana alone.

For example, BP faced a maximum fine of $13.4 billion for Clean Water Act violations based on the judge’s rulings on the amount of oil spilled and that “gross negligence” on the part of the company led to the accident.

However, the settlement allows BP to pay only $5.5 billion for the Clean Water Act fines.

The RESTORE Act, championed by Louisiana’s congressional delegation, will split 80 percent of that, or $4.4 billion, between the five Gulf states. Louisiana’s share comes to about $800 million.

The state always figured to do better under for the Natural Resources Damage Assessment, and it does.

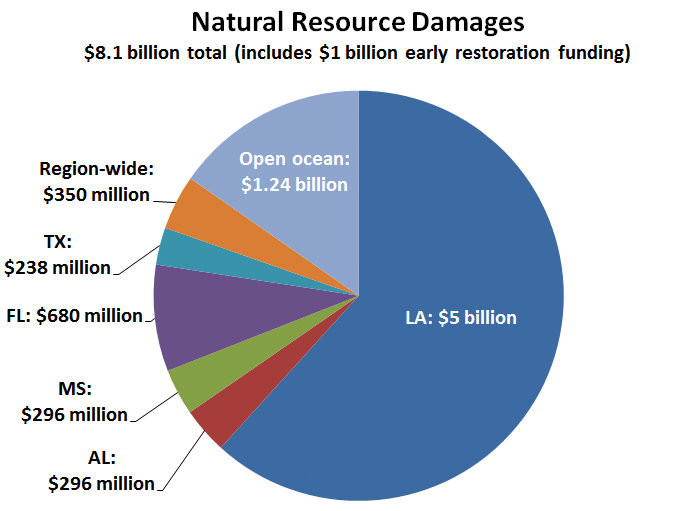

That process measures how much damage the oil did to fish, wildlife and wetlands, and presents the bill to the polluter. Some estimates put Louisiana’s possible take from a complete damage assessment — which was underway when the settlement was reached — as high as $12 billion. But the oil giant stopped that process by agreeing to pay $7.3 billion to all five states and the federal government.

Since most of the oil landed on Louisiana’s coast, it will receive 76.8 percent of that total, $5 billion.

Under the RESTORE Act, which was a political agreement among five states, Louisiana gets only about 34.6 percent — $457 million — of funds dedicated to repairing natural resources damaged by the oil.

Kyle Graham, executive director of the state’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority which runs the Master Plan, said Louisiana’s total receipts from all aspects of spill payments will amount to about $10 billion, $8.7 billion of which will be for coastal restoration.

That is far below the best-case scenario. But government representatives had this choice: Take $18.7 billion now or face the likelihood of a yearslong, appeal-laden fight from BP if they pushed for maximum penalties. .

Dalbom said such a choice is common in environmental cases involving large companies.

“It’s all part of the bargaining,” he said. “And there was likely some pressure from the governors and the [Obama] administration to get this done before they all leave office.

“So, all in all, the settlement isn’t a surprise.”

On the plus side, fears the windfall could be raided by politicians for other uses appear to be unfounded. Under the Oil Pollution Act, which guides the damage assessment and mitigation process, payments must be used to return damaged resources to the levels they would have reached if the spill had not occurred, or to increase public access to them.

Further, Graham said federal officials will be involved in developing the restoration projects in Louisiana, along with state agencies. These include Louisiana’s departments of Environmental Quality, Natural Resources, Wildlife and Fisheries, the Louisiana Oil Spill Response Coordinator and Graham’s coastal agency. Federal participation will come from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and Department of the Interior, which include agencies charged with protecting and managing migratory birds, marine fisheries and marine mammals, as well as federal lands that were harmed.

Graham said Louisiana’s coast was divided into five regions for the damage assessment: the Pontchartrain-Borgne area east of the Mississippi River; the Mississippi River delta; Barataria Basin; Terrebonne Basin and the area west of the Atchafalaya River.

He expects preliminary restoration plans to be submitted for public comment by the end of the year.

The state hopes to make the best use of the BP windfall by undertaking coastal-restoration projects in places where the oil-spill money can be used.

“There is a tremendous amount of overlap between the areas that were injured by this spill and the areas in which we are already looking to for restoration actions under the Master Plan,” Graham said. “I think you will see a desire by the state as well as by a lot of the feds to make that link.”