“Pave Our Lake.” That was a bumper sticker you saw in the 1990s — a joke, of course, popular with proto-hipsters feigning weariness with the environmentalist campaign to “Save Our Lake.”

“Pave Our Parks.” That could be the message of an ironic bumper sticker campaign among today’s (land use) hipsters. Only this time, it wouldn’t be a joke.

Unless the City Council takes action — perhaps as early as this Thursday’s meeting — you’ll likely be seeing a lot more pavement in local parks, along with restaurants, “amusement facilities,” and other intensive uses. And the public, the Planning Commission and the Council will only be able to stand by and watch as a bunch of fat cats and political appointees decide what goes where.

It’s time to send a message to the Council: Don’t let Ron Forman and his understudies write the Comprehensive Zoning Ordinance now verging on final approval. Instead, as the slogan goes: “Fix the CZO.” Don’t pave our parks.

First, a little history:

In 1974, about two years after Ron Forman was appointed City Hall liaison with Audubon Park, the Times-Picayune ran an editorial under the headline “Audubon Park ‘Disappearing.’ ” The paper lamented that the new zoo would “tak[e] away parkland devoted to casual public use” and reached the “inescapable conclusion” that “the front part of the park will have to be redesigned for traditional park use,” as the remaining land “will be too valuable to devote to a golf course’s low-intensity use.”

Park boards and commissions have a role to play in deciding whether to put new restaurants, golf courses, and amusement facilities in our parks, but so does the general public.

Ignoring the editorial advice, Audubon officials didn’t redesign the “front” of the park — i.e. the part between Magazine Street and St. Charles Avenue — to increase all-purpose green space. To the contrary, in 2002, led by Forman, whose private non-profit Audubon Nature Institute by then enjoyed a lucrative and exclusive contract to run the park, Audubon unveiled a plan to expand the golf course and put a golf clubhouse in the park’s largest oak grove, complete with a paved road and parking lot. Under the proposal, parkland once available for casual or passive general use would give way to roadways, buildings, cars and parking space. The quiet of the oak grove would yield to the rumble of air conditioning compressors.

A public uproar ensued.

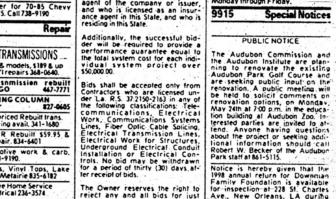

Critics complained that the primary public notice of Audubon’s planned golf course expansion was a postage stamp-sized classified posted in the Times-Picayune by Bob Becker, then Forman’s assistant. Audubon went into damage-control mode and hastily scheduled public hearings, but other than a few meaningless tweaks, Forman and company moved ahead with their plan to expand the golf course and push the general public to the borders of the park.

At the time, I represented the non-profit advocacy group Save Audubon Park in a suit questioning whether the restaurant in the clubhouse was legal, given that the zoning code allowed restaurants “within boundaries of a zoo only.” When Audubon initially unveiled its plans, it referred to the clubhouse restaurant as, well, a “restaurant.” But once our suit was filed, Audubon argued that the restaurant wasn’t a restaurant after all; according to Audubon’s newspeak, the former restaurant would thereafter be known as “food service in a clubhouse.”

We lost. You get used to losing public-interest lawsuits, particularly in state courts, which are inherently political. You keep going.

Fast forward to 2014, when Forman’s Audubon Nature Institute put a proposed millage on the ballot. A grassroots group, including some of us still angry at the Institute’s continued commercialization of the park, opposed the millage initiative. Among other things, we objected to Audubon’s grab for tax money while the city recreation department (NORD) and other parks went begging. When it came out that Audubon had cooked the books, misrepresenting what really was a tax increase as a “renewal” of an existing tax, the press, from the The Tribune to City Business, denounced the proposal, and voters zapped the millage.

Audubon’s tax millage debacle was followed shortly by protests over the new City Park golf course. February minutes of the City Park Improvement Association, the appointed board that runs the park, defend its decision to move forward with the course, claiming there have been five public meetings on its master plan since 2005 and that the land now being bulldozed for the new course was designated as a golf course at every hearing. What the minutes don’t say is that City Park’s own 2014 Master Plan — signed by Forman’s former understudy, Bob Becker, now CEO of City Park — still shows the area recently bulldozed for the golf course as being part of a “Nature Area.” Not surprisingly, opponents of the new City Park course claim there wasn’t sufficient public notice and have filed suit to stop construction.

Two things are clear. Citizens don’t want commercialization of parks, and they want adequate notice and opportunity for public input before major changes to parks are implemented.

The draft CZO pushes in the wrong direction, greasing the skids for commercial development in parks. First, it will broaden the range of permitted commercial and intensive uses of parkland, mainly by making restaurants — now allowed only in a zoo — to be “permitted uses” anywhere in our “regional” parks (Audubon, City, and Joe Brown). What this means is that once a park board has announced its development scheme, the City would be required to issue a permit for a new restaurant without further public review.

There’s a simple solution: Amend the CZO so that these “permitted” uses are designated as “conditional” uses. That would trigger the usual procedural safeguards:

- The proposed changes would have to be critiqued by professionals on the City Planning Commission.

- They would have to be heard by the Planning Commission, providing a first opportunity for public notice and public comment.

- They would then have to be approved by the Council, providing a second opportunity for public review.

Predictably, the proposed amendment is kicking up opposition in high places. Becker appeared before the Council last week to condemn “any effort to modify” the pertinent part of the CZO or to “restrict amount and number of permitted uses in these parks.” In other words, Becker doesn’t want development plans reviewed by anyone but members of his own board.

Other views of the CZOKeith Hardie: Wanted: Businesses sized to fit current zoning — not more parking lotsJohn Koeferl: Ripping the fabric of a neighborhood and with it the spirit of democracyKeith Hardie: Auto ‘rapture’ along Magazine Street? The CZO parking deregulation seems to count on itDiane Lease: City Council needs to redraft the CZO — too important not to get it right

The park boards and commissions have a role to play in deciding whether to put new restaurants, golf courses, and amusement facilities in our parks, but so does the general public. Given that the park boards haven’t always been straight with the public, and given the widespread perception that they don’t provide sufficient opportunity for public review of intensive new projects, what harm could result from an amendment that assures a more democratic process.

To recap: The Council should amend proposed Article 7, Section 7.2, Table 7.1 of the proposed CZO to make golf courses, country clubs, standard and specialty restaurants, live performance venues, reception facilities, catering kitchens, and amusement facilities conditional uses, subject to close scrutiny by the public — not something park boards can impose on us arbitrarily.

New Orleans native Keith Hardie is an attorney active in community fights over regulatory and land-use issues.