Reginika Tasso snorted at news that the number of vacant houses in New Orleans dropped over the past year by nearly 9,000 to a new post-Katrina low of 50,100. “Really…” the Central City-raised Harvey resident intoned. Did they count the house where I used to stay, asked Tasso, giving an incredulous eye to the reporter who delivered the Greater New Orleans Community Data Center pronouncement.

Tasso is a cashier at Aeren’s Cafe in Hoffman Triangle. On Monday afternoon, she stood alone in the small eatery, save for an elderly woman nursing a platter of fried shrimp and a man in the corner, behind a swinging door, playing video poker.

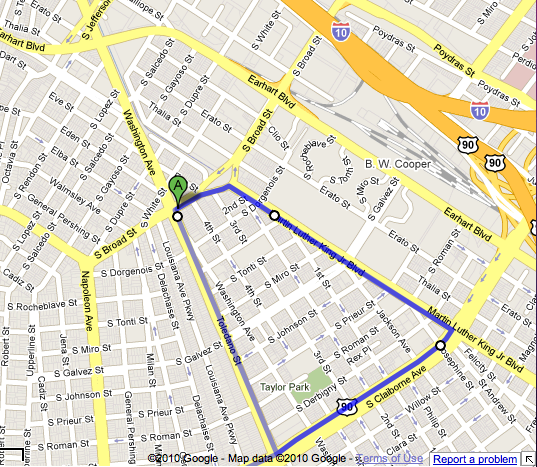

In this corner of Central City, empty tables, boarded buildings and the trash-dotted field of the former B.W. Cooper public housing development provided a dull counterpoint to the hopeful news that the amount of empty houses in New Orleans is on a slow but steady decline from the 65,400 vacant addresses counted just two years ago.

“It’s been, what, five years since Katrina? But it’s like the same here. If you take a drive down Washington Avenue it’s quiet. You hardly see any people,” Tasso said.

Most of her friends and family members moved to the West Bank suburbs of Gretna and Harvey, she said.

“I came back to work out here, to help a friend. There’s not really a reason to be living back here,” Tasso explained, gesturing toward her lone customer and the empty Washington Avenue parking lot beyond.

Hoffman Triangle, a long-neglected wedge of Central City, sits between the more affluent neighborhood of Broadmoor and the nearly abandoned B.W. Cooper. A report released last year by the Data Center pegged the rate of return in the public housing neighborhood at 27 percent, or 345 households compared to the 1,269 who lived in public housing buildings that closed after the storm. By the same time, Central City as a whole had welcomed back 76 percent of households or 6,223 out of 8,175 pre-storm, while bordering Broadmoor saw 74 percent of households — 2,324 out of 3,139—return.

Hoffman Triangle was neither flattened for recovery, like the housing project, nor nurtured back to health by homeowners. Instead, the small neighborhood has continued along the path it was on before the storm, one of quiet neglect interrupted by the hard work of a few committed community members, many of whom belong to the Hoffman Triangle Neighborhood Association.

Next to Aeren’s Café, owner Faris Canahuati runs a neighborhood grocery store, Aeren’s Supermarket. With a spare selection of plastic-wrapped sweets, fresh produce and pantry staples laid out in low utilitarian shelves, Aeron’s Washington Avenue grocery store represents one highly perishable front line on the battle to repopulate Hoffman.

“There aren’t enough people to buy a day’s shipment of milk anymore,” Canahuati said. He estimates that 25 percent of his customers never came back.

Canahuati is counting on change in the form of the progress on the stalled redevelopment of the B.W. Cooper site, and with the redevelopment of lots controlled by the New Orleans Redevelopment Authority.

All but forgotten by the grocer is coordinated “target zone” redevelopment promised for the area by former Recovery Czar Ed Blakely.

“When I first heard about that I went to the city trying to get help,” he said, talking loudly over the hum of refrigerators on the other side of his office wall. “I gave up real quick.”

Still up in the air is how Mayor Mitch Landrieu will implement the much-touted Blakely plan. No public announcements on a new recovery strategy have been made. In an interview last week, City Council President Arnie Fielkow said the council had not yet been briefed on a plan.

“I haven’t anyone talk about target zones in a good long while,” he said.