Pres Kabacoff was tooling around downtown in his black Lexus, expounding on his favorite subject: how to transform New Orleans into an Afro-Caribbean version of Paris.

Shorn of the ponytail he sported for more than a year – a casualty of his meetings with bankers this summer – Kabacoff riffed on how many of the elements for Paris-on-the-Mississippi already exist. At times, he sounded like a dreamy romantic, at other times like a calculating developer.

New Orleans has choice restaurants, the country’s greatest river, a thriving music scene, popular tourist attractions and historic neighborhoods, Kabacoff offered. And the city has become even more attractive in recent years, he said, with expanded streetcar lines and strengthened neighborhoods, particularly Faubourg Marigny, Bywater and the Warehouse District. It’s becoming a city amenable to walking and biking.

But the core of the city remains incomplete, Kabacoff added, and as he drove around downtown, he pointed out the sights: the monumental but abandoned Charity Hospital on Tulane Avenue, vacant lots two blocks away on Canal Street and the fenced-off Iberville housing development, a block from Canal, where reconstruction at last has begun.

But where others might see ruin, Kabacoff sees promise. He is sketching out a vision that stitches the pieces together: Iberville would become a mixed-income neighborhood. As Mayor Mitch Landrieu has proposed, City Hall would occupy one wing of Charity and the Civil District Court would take a second wing. The third wing, Kabacoff proposes, would house a neuroscience facility dedicated to advancing brain research for such diseases as Alzheimer’s.

The neuroscience facility idea is new, but it intrigues Cedric Grant, Landrieu’s deputy mayor for infrastructure projects. The facility, Grant said in an interview, “is very conceptual at this point. But I hope it comes together. It sounds like a fantastic opportunity for the city to build an industry.”

With thousands of new government workers, court officials and medical professionals at the renovated Charity and hundreds of new residents at a safe Iberville, national retailers would have a reason to invest downtown, Kabacoff figures. The vacant lots on Canal would become a New Orleans version of Lakeside Shopping Center and a magnet for locals and tourists.

And, he hopes, perhaps one day the elevated Interstate 10 nearby will come down, connecting downtown to Mid-City and the new Louisiana State University and Veterans Administration hospitals only blocks away.

“I don’t think of myself as an opportunist developer. I think of myself as on a mission.”—Pres Kabacoff

Together, all of the different pieces would cost more than $1 billion, Kabacoff estimates, but he doesn’t have a clear way to pay for them. Still, Kabacoff believes the projects would make a good investment for taxpayers because they would put a key area of New Orleans into commerce, attracting new residents, new shoppers and new businesses.

“The key word is transformation,” Kabacoff said in a separate interview at his home. “If we can make this area better, it will lift all boats.”

Kabacoff admitted that he’s not pushing the idea entirely for altruistic reasons. His company, HRI Properties, would be an obvious choice to oversee Charity’s renovation, he said.

“I don’t think of myself as an opportunist developer,” Kabacoff said. “I think of myself as on a mission.”

Whatever you think of him, Kabacoff and his vision face huge obstacles. There isn’t money to fully redevelop Iberville. Mayor Landrieu, the main proponent for moving City Hall and the Civil District Court into a refashioned Charity, hasn’t yet identified how to pay the estimated $300 million tab, and the judges pooh-pooh the plan. The neuroscience facility is just a fanciful idea at this point.

Without a revamped Charity and Iberville, plans for retail stores on Canal Street are but a hope.

Kabacoff is undeterred. “It’s not a pipe dream,” he said. “We’re on the road to success. I’m very optimistic.”

Developer has shifted focus throughout the city

Kabacoff, 68, has had big successes before. A New Orleans native who graduated from LSU law school, he assisted his father Lester in turning a vacant Mississippi River cargo wharf into the riverside wing of the Hilton hotel.

Kabacoff was among the pioneers in the Warehouse District beginning in the mid-1980s with his conversion of the Federal Fibre Mills building. Along the way, he has tapped government subsidies, frequently in the form of historic tax credits, to turn his projects into reality and make gobs of money.

In the 1990s, HRI got the contract to overhaul the St. Thomas housing development, just upriver of the Pontchartrain Expressway. Down went the brick buildings and up went pretty houses with porches – as well as a Wal-Mart superstore fought unsuccessfully by preservationists.

After Hurricane Katrina, Kabacoff turned his attention to Bywater, a once-forlorn neighborhood that was quickly gentrifying. He and his wife Sallie Ann Glassman – a voodoo priestess and artist – built a two-story house that is chock-full of her art and art from Mexico, Bali and Morocco.

“I hope that you don’t mind the lack of air conditioning,” he told two recent visitors, and excused himself to take a shower. He was sweaty after climbing stairs at his office in preparation for an upcoming hike up 19,000-foot Mount Kilimanjaro.

“Our physical city is the most important thing we have. It’s the foundation of our music, our culture and our food. If you don’t protect the physical fabric, you’ll irreparably harm the city.”—William Borah, a land use attorney

Kabacoff and Glassman turned the vacant Universal Furniture building on St. Claude Avenue into the New Orleans Healing Center, which features an organic restaurant and coffee shop, a nightclub, a grocery store, an art gallery and dance and yoga studios.

All along, Kabacoff nurtured the idea of transforming downtown New Orleans. In 2010, after chairing a housing task force for Landrieu’s transition team, he wrote a paper that he called Return to Splendor. Critics accused him of favoring the wealthy at the expense of the poor. He rewrote it.

The current version focuses on Iberville, Charity and Canal Street and wins him plaudits from business leaders.

“Pres understands you need things like parks and bike sharing,” said Kurt Weigle, who is president and chief executive officer of the Downtown Development District. “He works with us to create those things. He understands that development has to serve more than just the wealthy.”

Preservationists praise Kabacoff’s construction of the Healing Center and his support for dismantling the I-10 elevated highway. But they express their mistrust because of his push for the Wal-Mart. With its enormous parking lot and cookie-cutter design, they believe the Wal-Mart represents the antithesis of everything that makes New Orleans unique and wonderful.

“Big box stores in New Orleans are destructive,” said William Borah, a land use attorney who played a key role in stopping the riverfront expressway that political and civic leaders in the 1960s wanted to cut along the edge of the French Quarter.

“Our physical city is the most important thing we have. It’s the foundation of our music, our culture and our food,” Borah said. “If you don’t protect the physical fabric, you’ll irreparably harm the city.”

Iberville renovation under way

Iberville is the one project in Kabacoff’s plan where he can point to tangible progress.

Earlier this month, workers in hard hats began demolishing Iberville under a contract awarded to HRI by the Landrieu administration and the Housing Authority of New Orleans.

On a recent morning, Kabacoff stood by a chain-link fence with a “Keep Out” sign and explained the plan over the sound of hammering. The sprawling complex contains 820 units in 75 separate buildings. HRI is tearing down 59 buildings, keeping those on Bienville and Marais Streets to reintroduce the street grid.

890Mixed-income units planned in Iberville renovation227Units now funded

Once completed, Iberville would include about 890 units of mixed-income housing in new and renovated buildings owned by a partnership with HRI in charge.

The 400 or so remaining residents at Iberville are being relocated by HANO, Kabacoff said. Many of the elderly will move to the former Texaco building on Canal Street. It, too, is now owned by HRI and its partners.

Kabacoff said Iberville’s new buildings will have four floors and will evoke the Storyville era. Prices will accommodate a range of incomes, including former public housing residents, people making less than $30,000 per year and those willing to pay what the market will bear — perhaps $1,400 per month for a two-bedroom place.

“Density is good as long as you don’t concentrate the poor,” Kabacoff said, shifting into developer mode. Because Iberville abuts the French Quarter, “this is as good a location as you can have in New Orleans.”

He added, “This plan gives us the kinds of buildings you want.”

But HANO and HRI have enough money to build only 227 units. Plans call for more mixed-income housing as part of what’s known as the Choice Neighborhoods Initiative: approximately 660 more units at Iberville and another 1,500 units to be spread throughout downtown, Treme and part of Mid-City. Much of this housing will be apartment buildings and will require tens of millions of dollars more, Kabacoff said. Where will the money come from? He doesn’t yet know.

HRI has applied to the Louisiana Housing Corp. to finance another 75, Kabacoff said.

HANO’s senior officials would not be interviewed. The agency’s spokeswoman, Lesley Thomas, said only in an email “that there remains a funding gap to complete the Iberville project, which is the developers’ responsibility to close.”

Kabacoff offered a developer’s optimism: “You can sell more on the come. People who have avoided this part of town will say, ‘Gee, there’s been a change.’”

Charity as home to neuroscience center and City Hall?

No one would mistake the change at Charity if Landrieu could pull off his plan to move City Hall and the Civil District Court there. Both buildings suffer from leaks and balky elevators, and they are not equipped for the Internet age.

Charity, built in the 1930s with an Art Deco facade that makes architects swoon, was shut down after Katrina flooded its basement.

Steve McDaniel is a Philadelphia-based architect who analyzed the building after Katrina for the Foundation for a Historical Louisiana. Now working on Kabacoff’s plan, McDaniel said Charity remains structurally sound and could have reopened after Katrina. But LSU and state officials decided to build a new hospital elsewhere.

“The building can be refigured,” said Cedric Grant, the deputy mayor. “If you can get the right tenants, it can work.”

In Landrieu’s conception for what he calls the Civic Center, Charity’s main entrance on Tulane Avenue would become the main entrance to City Hall. But City Hall would take up only about 40 percent of the building, and Landrieu has not proposed a use for Charity’s riverside wing.

Kabacoff’s pitch: Have it house publicly-financed doctors and scientists, as well as private start-up companies doing pioneering research into treating brain disorders.

He has the enthusiastic backing of Dr. Nicolas Bazan, a professor at LSU’s Health Science Center in New Orleans and director of its Neuroscience Center of Excellence. Bazan believes the time is ripe for such a research center. In April, President Obama called for spending $100 million to advance brain research.

The biggest risk factor for Alzheimer’s is age, Bazan said. “We cannot do anything for them. The number of patients is growing. If you can put together research minds, the care of patients will be enhanced. Prestigious doctors will come here. Start-up companies will come.”

Dr. Keith Van Meter, who heads LSU’s emergency medicine section, said he would work with Bazan and Kabacoff to create a lab to research the use of hyperbaric chambers in treating trauma victims. (Any clinical trials would take place at the new LSU hospital.)

In his office at West Jefferson Medical Center, Van Meter said doctors in the New Orleans area have made great strides over the past 40 years in using hyperbaric chambers to keep alive divers injured in offshore platform oil and gas accidents. Van Meter believes that hospitals around the country will soon use that knowledge to install hyperbaric chambers to treat victims of heart attacks, gunshot wounds and car crashes.

“If we can keep the heart pumping with a meaningful amount of oxygen,” he said, “then we can keep the brain more viable.”

Van Meter envisions New Orleans capitalizing on its pace-setting role. The Department of Defense could finance research that would improve treatment of soldiers injured in battle, he said. Oil companies would be willing to finance further research, he believes.

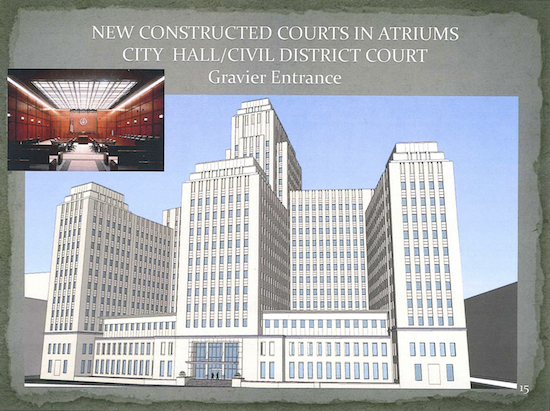

A plan for putting courts at Charity

Landrieu’s plan calls for Civil District Court to have a separate entrance in Charity’s lakeside wing, to address the judges’ concern that the city’s executive and judicial branches should not be intermingled.

[module align=”right” width=”half” type=”pull-quote”]What are the chances that the judges will move to Charity? “Zip. Zero. Nada. Not at all. Won’t happen,” said Civil District Judge Michael Bagneris.[/module]Judges Michael Bagneris and Kern Reese, sitting in Bagneris’ cramped office at the court next to City Hall, said Landrieu’s plan is unworkable because Charity’s columns obstruct the view inside the courtrooms. An architect hired by Kabacoff came up with a solution: 14 column-free courtrooms could be built between the two wings, along with judges’ chambers and jury rooms.

Kabacoff showed his plan to several judges, but Bagneris and Reese remain unmoved. They want a new courthouse on a patch of grass in Duncan Plaza that was formerly the site of a state building and the state Supreme Court. It would cost about $105 million, Reese said.

“We have the ability to raise the funds,” Bagneris said, by increasing court fees from $25 to $200 per filing, issuing bonds, building a parking garage and obtaining federal New Markets tax credits. He and Reese said the judges could move forward once the court and the state, which owns the land, work out an agreement.

$300 millionFor City Hall, courts and neuroscience center at Charity40%Of building would be occupied by City Hall

Kabacoff, however, believes that the judges cannot raise enough money from selling bonds and that the parking garage would cost rather than contribute funds for a new courthouse. “The judges would be smart to buy into the mayor’s vision of co-locating in Charity, which will result, I believe, in achieving the financing they need for a new courthouse.”

What are the chances that the judges will move to Charity? “Zip. Zero. Nada. Not at all,” Bagneris said. “Won’t happen.”

In response, Grant said: “We’re proceeding with our idea. Who’s in it, who’s not – we’ll work through that.”

The two sides, though, are discussing meeting on Friday, said Walt Pierce, a spokesman for the Civil District Court.

Grant said the Landrieu administration could finance Charity with state, FEMA and federal hazardous mitigation money.

The Jindal administration is not making any promises for now.

“We’ve always supported the re-development of Old Charity, and we support a feasibility study,” Kristy Nichols, the state Commissioner of Administration, wrote in an email. “We’re working with the city to determine the full needs of the project.”

What would happen to the current City Hall and Civil District Court? In separate interviews, Kabacoff and Grant said the site could be a prime location for a hotel or some other development.

New retail development on Canal

The final piece of Kabacoff’s puzzle centers on two full blocks – one on each side of Canal Street – owned by the Coleman family, which has major real estate holdings in New Orleans. The Colemans and a Dallas-based real estate company have sketched out a retail project there called Canal Crossing.

“We’re motivated to the extent possible to bring a great new project to this part of Canal. But it’s too early for putting the pieces together.”—David A. Garcia, point person for Canal Crossing project

It would have retail stores on the two ground floors — 300,000 square feet total — topped by three floors of parking with 1,000 spaces, said David A. Garcia, the son-in-law of Peter Coleman and the project’s point person. He put the total cost at $100 million, but added that the price tag would rise if the Colemans decided to put apartments or condos above the parking levels.

“It’s rare to have large parcels downtown,” Garcia said in an interview. “We’re motivated to the extent possible to bring a great new project to this part of Canal. But it’s too early for putting the pieces together.”

The national retailers, he said, won’t consider coming until the area has a critical mass of potential shoppers. That has no chance of happening unless Charity and Iberville are refashioned, Garcia said.

As he was driving around downtown, Kabacoff made an offhand remark. “I could have done more damn McDonald’s in the suburbs. This is not for the faint-hearted.”

Several minutes later, discussing the three parts of his plan, he said, “It’s all in play.”

Told that he sounds like a developer, he replied, “I am a developer.”

A short time later, he added, “This is the swan song for me. I’m getting to be an old hoot.”