Exactly what are we to commemorate on June 19, our newest federal holiday?

Juneteenth, the poetic contraction of the date that gives the holiday its name, was initially celebrated mostly among black Texans as a commemoration of that day in 1865 when news of President Abraham Lincoln’s 1862 Emancipation Proclamation reached people enslaved in the southern part of their state.

For decades, Opal Lee, the 97-year-old “grandmother of Juneteenth,” fought to have the date recognized as a federal holiday. In 2021 President Joe Biden made it official. Earlier this year, he awarded Ms. Lee a Medal of Honor to acknowledge her role.

“Juneteenth is a day of profound, profound weight and power to remember the original sin of slavery and the extraordinary capacity to emerge from the most painful moments with a better vision of ourselves,” Biden said. “Ms. Opal Lee made it her mission to make history, not erase it. And we’re a better nation because of you, Opal. Thank you.”

That it took two-and-a-half years for news of the Emancipation Proclamation to reach people enslaved in southern Texas and another 156 years for the nation to take official note of this injustice is a fitting metaphor for all Americans who have suffered the outrageous fortune of justice delayed. Women, who had to wait until 1920, when the 19th Amendment granted them suffrage, can claim a kind of kinship to the Juneteenth holiday. So can Japanese Americans who waited more than four decades for the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 to acknowledge the “grave injustice” and grant them reparations for the evils of their internment during World War II. So can gay Americans who had to wait until a Supreme Court ruling in 2015 for the right to marry the person of their choice.

These belated acknowledgements of past American injustices are a kind of rewriting of our history. Not the facts of it, but the interpretation of it.

As a New Orleanian, the Juneteenth holiday is a reminder to me of a recent, and thus far mostly failed, attempt to reinterpret our history. “On June 18, 2020, the New Orleans City Council approved Motion M-20-170, authored by Councilmembers Kristin Gisleson Palmer and Jay H. Banks to establish the City Council Street Renaming Commission, an advisory committee to consider renaming certain streets, parks and public places in New Orleans that honor white supremacists.”

In the roughly three years since the commission issued its recommendation, about a half dozen of the suggested streets have been renamed. The city council has failed to take any action on the vast majority of the recommendations of its own commission.

There will certainly be Juneteenth commemorations in New Orleans, but I fear that they will be generic celebrations of emancipation rather than specific events related to the history of slavery and the post-slavery struggles here in New Orleans.

If the heroes of New Orleans culture and freedom are not commemorated here, where will they be remembered?

Herman Midlo funded the Midlo Center at the University of New Orleans specifically for the study of our city and local heroes. People like Juan San Malo, who helped lead a maroon community of escaped slaves in the 1700s; Elanora Peete, who in 1918 founded the Domestic Workers Union, which represented the interests of a large swath of black working women; Rodolphe Desdunes, whose book “Nos Hommes et Nos Histoire” — “Our People, Our History” — was one of the few accounts of the efforts of black people in the 1800s to provide education and voting rights to all New Orlenians.

Each of these people are being considered for the honor of having a street named after them. Each is worthy.

Much like the official Juneteenth holiday, the renaming of these streets would represent a reinterpretation of our history.

While no current action could undo the stench that our city’s white supremacists bequeathed to us, removing their names from places of honor would be an affirmative statement that their values are not our own. It would be a way of disassociating ourselves from New Orleanians and others whose legacies are best disdained and discarded.

Which leaves us with a question: What does the failure to act on the recommendations of the renaming commission mean for our city?

I am more than a disinterested party in this matter. The commission proposed that my father’s name be among those considered to replace a current street name. If this change is enacted, “Lolis Edward Elie” would be the name given to the street running through the French Quarter and Faubourg Treme, in place of the name “Gov. Nicholls,” a Confederate general who was elected governor of Louisiana after Reconstruction.

My father knew the entire span of Gov. Nicholls, from the Quarter to its endpoint at North Broad Street. For much of my childhood, my father lived at 715 Gov. Nicholls St. in the upstairs half of a house owned by James Dombrowski, the Christian socialist minister who worked with the organizers of the Montgomery Alabama bus boycott and whose 1965 Supreme Court case essentially struck down Louisiana’s Subversive Activities and Communist Front Control Law.

Later, when my father moved to Faubourg Treme, he never lived more than a block away from Gov. Nicholls Street.

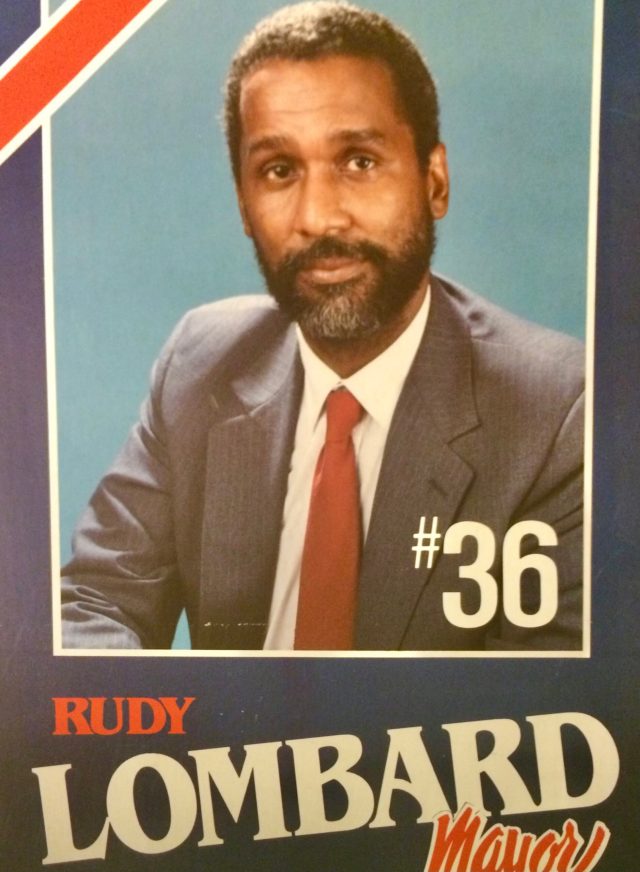

My father engaged in civil rights work reluctantly at first, preferring to focus his then-fledgling legal career on the goal of supporting his young family. But Rudy Lombard, an early chair of the New Orleans chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), whose name is also being considered for a street renaming, asked my father if he would represent the students planning sit-ins at segregated lunch counters on Canal Street. My father recruited his friend Jack Nelson to represent the demonstrators before becoming immersed in the movement himself.

The street re-naming recommendations also included my dad’s former client, his dear friend Rudy Lombard, whose civil-rights work evolved several times, leading him to become a food historian; an author of the 1976 Claiborne Design Team study that reenvisioned Claiborne Avenue and surrounding corridors; a 1986 candidate for mayor of New Orleans; and a moving force behind the Neighborhood Development Foundation.

Jack Nelson’s name is also being considered for a street.

At my father’s funeral, retired Criminal Court Judge Calvin Johnson fondly remembers the courageous efforts my father made in defending him and several other teenaged civil rights demonstrators in Plaquemines, Johnson’s hometown. Decades after the fact, the two men had what amounted to a two-line comedy routine. “You lost my case!” Judge Johnson complained. “You never paid me!” my father retorted.

My father was proud of the fact that he continued his efforts on behalf of racial equality long after the 1960s. In one of his most famous efforts, he and a team of lawyers secured acquittals for members of the Black Panther Party accused of the attempted murder of police officers in the Desire public housing project.

Over a lifetime, his work was part of a determined effort to ensure that the ideals and laws of the United States Constitution would be upheld in Louisiana.

These ideals are far larger than any one man and the council’s failure to act is an affront, not so much to me and my family, but to the very notion of the ideals the council should hold dear.

Optimally, the council would have acted on the recommendations of its commission with all deliberate speed. Having failed that test, the Juneteenth holiday should serve as a reminder that the council should still act. And it should act now.

Lolis Eric Elie is a former board member of The Lens and a former columnist for The Times-Picayune.