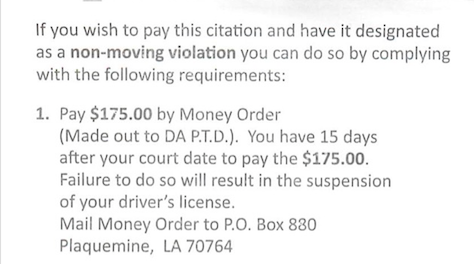

Jay Dixon was heading home from Baton Rouge to Lafayette one day when he got pulled over for speeding. As the deputy handed him the ticket, Dixon said, he was told to flip it over. On the back, Dixon found instructions saying he could pay the ticket by mailing a $175 money order made out to “DA P.T.D.”

If he paid the ticket that way, the deputy told him, it wouldn’t go on his record. Plus, it wouldn’t go through court, so he wouldn’t have to pay court costs.

“Who wouldn’t want to do it?” Dixon asked as he recounted what happened.

“P.T.D.” stands for Pre-Trial Diversion, and it’s an increasingly common sight on traffic tickets in Louisiana, according to research by The Lens. These fines do not go through the court system, which divides revenue among several agencies. Instead, the money goes straight to the district attorney.

Historically, pretrial diversion programs have been used to “divert” criminal defendants to drug rehab and counseling programs. The goal is to keep nonviolent offenders out of jail, address problems that contribute to crime, and reduce jail costs.

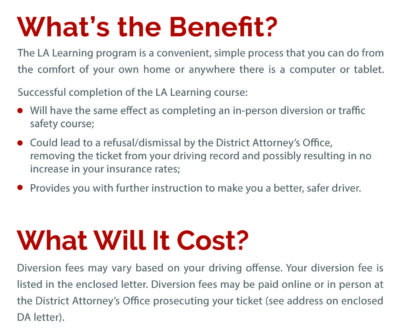

But diverting traffic tickets is a newer phenomenon, according to prosecutors and public defenders in Louisiana. Offenders are spared not from jail time, but from higher insurance premiums that could result from speeding tickets.

Some jurisdictions, like West Baton Rouge Parish where Dixon was pulled over, simply require drivers to pay the DA’s office. Others, like St. Bernard Parish, also require them to complete an online class or read a pamphlet on safe driving.

Dixon, it so happens, is familiar with this system. As the State Public Defender, he fields requests for money from underfunded public defenders all over Louisiana — some mundane, some desperate. Several have told him their budgets have been hurt by pretrial diversion programs for traffic tickets.

Louisiana is the only state where public defenders depend largely on traffic tickets for their funding. Their budgets have been shrinking for years for a few reasons; primary among them is a drop in the number of traffic tickets processed in court.

Some public defenders say traffic diversion is one reason for fewer tickets.

Public defenders in nearly a dozen judicial districts, including in New Orleans, are refusing cases because they say they can’t properly defend people with their limited resources. Others have cut back on staff, training or equipment.

The Plaquemines Parish public defender’s office, just south of New Orleans, shuttered its office in Belle Chasse for a few days last year until Dixon bailed them out with emergency funding.

The head public defender in Calcasieu Parish, over on the Texas border, has watched his office shrink. Harry Fontenot says he knows why.

“See, it all started when we tried to get a raise,” he said.

Public defenders get more funding, but revenues fall

Five years ago, public defenders in Louisiana managed to convince state legislators they needed more than the $35 allotted to them from each court case.

“We let them steal less money than they were gonna steal from us.”—E. Pete Adams, Louisiana District Attorneys Association

Every person ticketed, fined or sentenced in Louisiana is required to pay court costs, which go to the sheriff, the court and other agencies. Public defenders rely on court costs for the majority of their funding.

Public defenders asked legislators for $100 from each case, nearly triple their previous cut, Fontenot said. That was whittled down to $45 after prosecutors and sheriffs associations protested.

“That was a theft of our portion of the fines and forfeitures,” E. Pete Adams, executive director of the Louisiana District Attorneys Association, said. “We let them steal less money than they were gonna steal from us.”

“Every year when I do a budget, I may as well be at the roulette table.”—Pamela Smart, Caddo Parish Public Defender Office

However, the law didn’t shift money from prosecutors to public defenders; it raised the fee for public defenders.

Adams said prosecutors opposed the increase because in the past, raising court costs hasn’t brought in more money. In fact, he said, the collection of court costs has gone down in the five years since that law was passed.

Other agencies, such as public defenders and court clerks, agree that collections are down, but say it’s due to diversion programs.

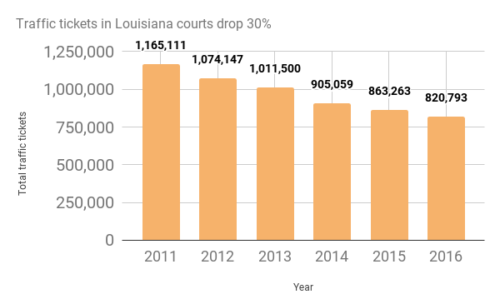

Dixon said public defenders expected to see a 30 percent increase in local revenue. Instead, the number of tickets filed statewide dropped 30 percent over the next few years, according to reports by the Louisiana Supreme Court.

+30%Revenue expected by public defenders after the law was passed-30%Drop in tickets that actually occurred, resulting in less revenue

Pamela Smart was the head public defender in Bossier Parish at the time. After the law went into effect, she said, the district attorney started to divert offenders into programs in which court costs weren’t collected.

Some months, she said, there were half as many traffic tickets in court as before.

Smart has since moved across the river to Shreveport, where she sits in an office overlooking the city and the casino. Local funding is uneven there, too. “Every year when I do a budget, I may as well be at the roulette table,” she said.

The Bossier Parish District Attorney’s Office did not respond to inquiries or a public records request from The Lens. Nor did it respond to an inquiry from the state legislative auditor regarding its local revenue.

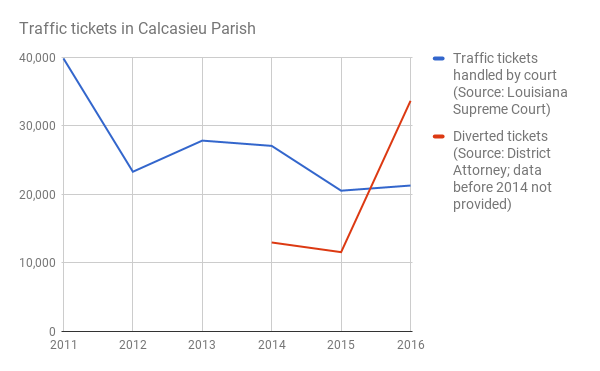

In Calcasieu, where Fontenot works, the local courts started to see fewer tickets the very month the law went into effect. From 2011 to 2012, the number of tickets dropped by 42 percent, according to Louisiana Supreme Court reports.*

Meanwhile, diverted tickets — the ones that fund only the DA’s office — nearly tripled in Calcasieu from 2014 to 2016.

After emails back and forth, the Calcasieu DA’s office told The Lens they couldn’t calculate their revenue or caseloads from before 2014.

Diversion fees there start at $125 for going 5 mph over the speed limit. A less serious violation, like an expired sticker, costs $100.

42%Drop in tickets in Calcasieu Parish from one year to the next3xAs many tickets were diverted there in 2016 than 2014

Traffic diversions grow as tickets in courthouses dwindle

The state doesn’t track local traffic diversion programs, which makes it hard to measure their growth.

The Lens asked seven district attorneys, covering 11 parishes, for records on their traffic diversion programs. Those DAs are diverting as many as half of their traffic tickets, according to the records. Several said their programs are growing.

Meanwhile, the courts in most of those judicial districts are handling fewer tickets. Statewide, there has been a 30 percent drop in tickets processed by courts over the past five years, according to data collected by the state Supreme Court.

In East and West Feliciana parishes, the number of traffic tickets processed in court has fallen 35 percent in the last five years.

The local district attorney has diverted about half of all tickets since 2013, according to public records.

District Attorney Sam D’Aquilla acknowledged his program keeps money out of the court system, but he said he needs it. For instance, one program requires his office to pay officers overtime for working extra hours to write traffic tickets.

“And that’s kind of why we started the diversion program, we just weren’t making the money,” he said.

Unlike criminal diversions, his office keeps all the money from its traffic diversion program.

D’Aquilla said he doesn’t know exactly how much the program has grown each year, but it was enough that he had to hire someone to handle them. “It’s an industry that we created,” he said.

Public records provided by other district attorneys show the same trend. In 2011, the Plaquemines Parish DA diverted only 22 traffic tickets. Last year, it was 278.

22Tickets were diverted in Plaquemines Parish in 2011278Were diverted there in 2016

The Avoyelles DA has diverted nearly half its tickets every year since 2012, prompting a state representative to ask where the money was going.

The district attorneys in Orleans and Jefferson parishes don’t run traffic diversion programs, although tickets have dropped significantly. In New Orleans, that’s due to the police department’s decision to move officers from traffic enforcement as it deals with understaffing.

St. Bernard Parish was the only judicial district to report a slight decline. The district attorney there started a program in 2015, diverting about one out of every five tickets. Last year, it diverted fewer tickets, and the office saw a slight drop in revenue.

The district attorney for Bossier and Webster parishes has not responded to a public-records request.

A growing industry goes mostly untracked

That district attorney also didn’t respond to a state study attempting to determine how much DAs bring in from local sources, including criminal and traffic diversion programs.

In the end, the Louisiana Legislative Auditor said it was unable to definitively say how much money they raised.

For instance, the Calcasieu Parish DA didn’t report any diversion revenue in 2014, but records provided to The Lens showed more than $800,000 in diversion fees that year.

One DA’s website claims 35 of the state’s 42 judicial districts run diversion programs, although it doesn’t specify whether they’re for traffic tickets or criminal offenses.

Adventfs.com, a Kentucky-based company, said six of its 10 clients in Louisiana now have online traffic diversion programs. The company creates online classes for offenders, quizzing them on driving safety and regulations.

Josh Hartlage, president and founder of Adventfs.com, said demand for its service has been growing in Louisiana and around the country.

The Louisiana District Attorneys Association is working to develop its own online program for prosecutors who can’t afford to do it themselves, Adams said. He said the goal is to teach better driving habits, prevent wrecks and reduce insurance premiums.

Getting a speeding ticket can raise your insurance premium by more than 10 percent, according to a survey by an insurance industry group — although another survey found that most drivers didn’t see a rate hike at all.

Some public defenders in Louisiana see these diversion programs as a cash grab. “My problem is, he’s taking our money, and we need it to survive,” Fontenot said.

Shortly after the public defenders got their law passed and tickets started falling, Fontenot had to cut loose several attorneys who were working on a contract basis.

In their place, judges ordered private attorneys — some with no experience in criminal law — to represent Fontenot’s clients. Some of them were volunteers, but many were not paid for the work.

The state Public Defender Board agreed last year to allocate more money to local judicial districts. Two-thirds of its budget now goes directly to parishes like Calcasieu.

Support for this story was provided by The Fund for Investigative Journalism and Investigative Reporters and Editors.

*Correction: This story originally reported that tickets processed in Calcasieu Parish court dropped by half from 2011 to 2012. It’s actually 42 percent. (July 27, 2017)