The 2017 draft version of the Coastal Master Plan, released today, offers a much grimmer view of the future than its predecessors. Twice as much land could be lost if the state does nothing. Even if everything works as planned, about 27,000 buildings may have to be elevated, flood-proofed or bought out, including about 5,900 in St. Tammany.

For 10 years, Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan has represented the state’s vision for preventing its bottom third from being consumed by the Gulf of Mexico.

That vision got a lot grimmer today with the release of the 2017 edition of the plan.

It predicts that even if everything works as planned, 2,800 square miles of coast still could be lost in the next four decades, and about 27,000 buildings may need to be floodproofed, elevated or bought out, including about 10,000 in communities around New Orleans. That’s under the plan’s new worst-case scenario for sea level rise and subsidence.

About 5,900 of those are in St. Tammany, including Mandeville, Covington and Slidell. That includes about 900 that may need to be bought out.

The new plan also has dropped the long-held claim that the state would be building more land than it’s losing by 2065.

Scientists in charge of the Coastal Master Plan said the more dire outlook can be traced to one striking fact: The worst-case scenario for human-caused sea level rise in the 2012 plan, 1.48 feet, has become the best-case scenario in the 2017 edition. In fact, the National Climate Assessment now estimates sea levels on U.S. coastlines could rise 4 feet by 2100.

1.48 feetWorst-case for sea level rise in 2012 Master Plan4 feetCurrent projection for U.S. coastlines by National Climate Assessment

“When we put those forecasts into the models, there’s less we can accomplish,” said Bren Haase, head of planning and research at the state Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority.

The new worst-case scenario projects that 4,000 square miles would be lost if the state stops all efforts to restore its crumbling, sinking coastal landscape. That’s double the loss projected in the same scenario in the 2012 plan.

However, the latest plan retains hope of restoring 800 to 1,200 square miles of wetlands and beefing up protection against hurricane storm surges with levees and floodwalls.

A changing plan in the face of darkening skies

The master plan was conceived in 2007 after Hurricane Katrina raised awareness of the vital role coastal wetlands can play in storm surge protection. The plan is updated every five years to reflect evolving science on how to address the two ongoing changes to the landscape: sinking of the sediment-starved deltas and rising sea level due to climate change.

Each plan is constructed by coastal scientists and engineers from the state and an array of federal agencies, with input from a wide range of stakeholders, such as the shipping and fishing industries.

The 2017 draft plan incorporates that input and is now out for review by the general public.

Each plan must be approved by the Legislature, but lawmakers cannot amend it; they can only vote it up or down. They unanimously approved the versions in 2007 and 2012.

The original price tag was $50 billion, but the current cost is about $92 billion after accounting for inflation, according to a study by Tulane University. Current funding can carry the plan forward for another 10 years.

Losing Ground: Southeast Louisiana is Disappearing, QuicklyScientists say one of the greatest environmental and economic disasters in the nation’s history—the rapid land loss occurring in the Mississippi Delta—is rushing toward a catastrophic conclusion. ProPublica and The Lens explore why it’s happening and what we’ll all lose if nothing is done to stop it.Louisiana’s Moon ShotThe state hopes to save its rapidly disappearing coastline with a 50-year, $50 billion plan based on science that’s never been tested and money it doesn’t have. What could go wrong?

Half of the plan addresses the crumbling coastal landmass, nearly 2,000 square miles of which has turned to open water since the 1930s. Primary causes include river levees, which have blocked the deltas from being replenished by sediment and caused the land to sink; canal dredging for oil and gas drilling; geologic faults; and now accelerating sea level rise due to global warming.

The other half of the plan focuses on protecting communities from flooding. Some of that is used for levees and floodwalls. Another portion helps property owners and communities adapt to higher flood risks by floodproofing buildings and elevating homes.

A great deal of progress has been made since 2007: 135 projects have been completed or funded, restoring or protecting 31,000 acres of land, according to the state. That includes improvements to 50 miles of barrier islands and 275 miles of levees.

Equally important, groundbreaking research has been completed to give planners a better understanding of how much building material the river can supply, and how much of the wetlands can be saved or rebuilt.

But those accomplishments have been overshadowed by the steadily increasing rate of sea level rise as greenhouse gas emissions warm the oceans and melt ice fields and glaciers.

That new reality of global warming is behind the most significant changes in the updated plan: There’s more attention and money to address the greater risks of flooding that come with higher sea levels and storm surges.

Planners identify communities most at risk for flooding

The 2012 said the state would develop a plan for a “limited number” of voluntary buyouts.

In the 2017 draft, an entire section is devoted to “Flood Risk and Resilience.” It calls for spending up to $6 billion to protect — and in some cases, vacate — properties in areas that can expect flooding during the so-called 100-year storm.

Such a storm has a 1 percent chance of happening in any year. That’s the level of protection provided by the upgraded levee system around metro New Orleans, and it’s the threshold banks use to require flood insurance on mortgaged properties.

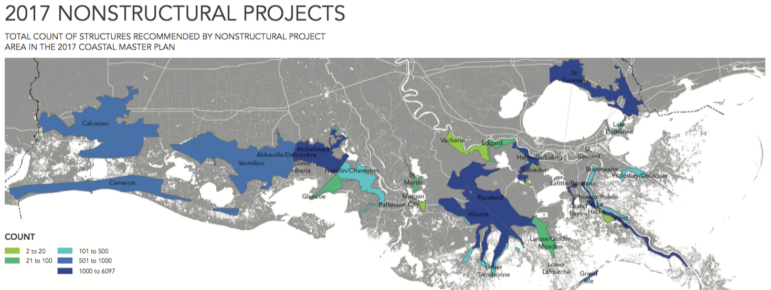

The agency says under the current worst-case scenario for sea-level rise, about 27,000 structures in 32 areas along the coast would qualify for one of three types of assistance depending on how badly they would flood. That’s even if the state achieves everything it sets out to do.

The communities include much of the North Shore of Lake Pontchartrain, Houma, towns on the west bank of the river in Plaquemines Parish, and a swath of communities stretching from Lake Charles to Morgan City.

In areas where flooding could reach 3 to 14 feet, the state would pay to elevate homes. There are about 23,000 structures in this group.

In areas where flooding could be over 14 feet, homes would qualify for voluntary buyouts. There are about 2,400 structures in this group; about 900 are in St. Tammany Parish.

In areas where flooding would be three feet or less, non-residential structures would qualify for flood-proofing, such as low berms or floodwalls around the property. About 1,400 buildings are in that group, according to the state.

About 10,000 of the affected structures are in and around New Orleans:

- St. Tammany Parish: about 5,900

- Jefferson: about 1,800

- Plaquemines: about 1,900

- Orleans: About 270

- St. Bernard: About 125

Haase said planners have not identified specific structures that would be floodproofed, raised or bought out. The figures were obtained by counting the total number of buildings at each elevation.

While the project calls for starting these programs immediately, Haase said there is no funding.

State pushes forward with plans to rebuild wetlands

Meanwhile, the wetlands restoration portion of the plan will continue to focus on two strategies.

Marsh creation involves dredging and pumping sediment from the river and offshore locations into marshes and barrier islands. More than 50 miles of shoreline on barrier islands have been rebuilt so far, as well as several hundred acres of marshes on the west side of the Mississippi River south of New Orleans.

The draft 2017 plan calls for spending $17.1 billion on much larger projects of this type.

Another $5.1 billion is earmarked for river sediment diversions. Gates will be installed at key points in the levee along the Mississippi to allow the current to carry sediment into the wetlands when the river is high.

The first, at Myrtle Grove about 30 miles south of New Orleans, is expected to be operational in about five years.

Five diversions had long been planned on the lower river, but the Lower Barataria Bay Project, located on the west bank of southern Plaquemines Parish, is gone from the 2017 plan. Haase said rising sea level and subsidence meant the project could not achieve its land-building goals.

Beyond climate change, the greatest challenge to the program is still money. For the past 10 years, most of the coastal restoration money has been spent on research, engineering and planning for the larger projects. The time is drawing near when the state will need billions more for construction.

The largest dependable source is the $500 million the state will receive annually for the next 15 years from various legal settlements stemming from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

The second is a portion of mineral royalties from federal offshore waters; that could bring $130 to $175 million annually through 2050.

That leaves the state well short of what it needs to achieve its goals.

State coastal restoration officials have said if they don’t have the money to enact the plan as written, Louisiana will end up with a smaller coast — and that will cause social and economic losses.

A paper by Louisiana State University and the RAND Corporation last year put those losses as high as $133 billion over 50 years.