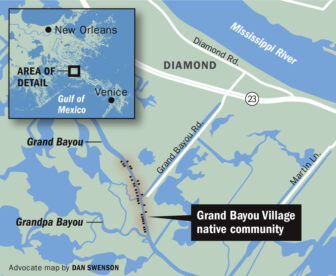

Like many Louisiana coastal residents, the Native Americans of Grand Bayou village have seen the landscape surrounding their community collapse over the past 50 years. The lush, freshwater wetlands and high ground that sustained them for centuries is now a ragged patchwork of crumbling salt marshes and expanding lagoons.

But unlike some other communities, these 40 residents of Plaquemines Parish don’t see the state’s 50-year, $92 billion coastal-restoration effort as a solution. They see it as the latest in a long string of injustices.

That’s because there are no projects to rebuild their wetlands — a habitat essential to their livelihoods and culture — even though they were destroyed by state-sanctioned activities.

“The only thing they offer us is to move — but we can’t move,” said Rosina Philippe, 60, an elder and spokeswoman for the Atakapas-Ishak/Chawasha tribe.* “For us, home is more than the building you live in. It’s everything in the environment that surrounds you. If you leave, you become someone else. You are no longer the same person. No longer the same people.

“That would kill our culture and our future entirely.”

At a minimum, they would like government help to determine ways they can continue to live in the wetlands. At best, Philippe said, those responsible for damaging the land would repair it. Neither is likely.

When Louisiana unveiled its ambitious coastal-restoration plan in 2007, it didn’t avoid an unpleasant bottom line: Many small coastal communities would fall outside the cost-benefit line for restoration and protection. Raising levees and rebuilding wetlands is expensive. The projects will go where they benefit the most people.

“They say we are a ‘high risk’ community,” Philippe said.

“But how did we become high risk, and who was responsible for that? The industries that destroyed the environment we need to survive, and the people who work for them, they are being protected but we are not.”

PARADISE LOST

That judgment was a blow to all towns on the wrong side of the line, but an especially harsh punch for the Native American communities. They believe no residents have a more valid claim for state aid in addressing the crisis than the native people.

They see history on their side.

Native people had been living on the great delta of the Mississippi River for many centuries when the first Europeans began settling here in the early 1700s. The oral history Philippe’s ancestors passed down tell the story of one band of natives who settled along the banks of a bayou peeling off the western side of the river about 35 miles south of what would become New Orleans.

“This was a paradise,” she said. “There were forests on the high ground with plenty of game. There were ducks and fish in the marshes and the lakes and bayous. There was everything they could ever want.”

Over centuries, the big river’s annual floods of fresh water and sediment flowing through distributaries like Grand Bayou had built 6,000 square miles of land into the Gulf of Mexico.

Philippe’s grandparents told her about a community of almost 1,000 in the 1940s, living in houses stretching five miles along the bayou banks and the natural ridges. Their livelihoods came from the land, harvesting shrimp, oysters and fish, trapping furbearers, hunting waterfowl and deer, raising livestock in pastures.

But the ancestors of those newcomers who arrived in the 1700s had already begun making changes to the landscape that would put an end to most of that.

The levees their governments raised on the river to protect cities and help shipping also stopped the flow of fresh water and sediment into the surrounding delta. That guaranteed the delta would sink and die over the coming centuries.

And those same governments also compressed that demise into a few short decades by allowing thousands of miles of canals to be dredged for oil and gas — never enforcing the rules requiring companies to repair any damage they caused. And they caused a lot: Studies estimate the canals are responsible for up to 60 percent of the nearly 2,000 square miles of coastal wetlands lost since the 1930s.

Louisiana’s coastal zone, including marshes, swamps and uplands, was turning to open water in some areas at rates as high as 50 square miles a year from the 1950s through the 1970s.

“When I was a child, there was still plenty of woods and forests, plenty of high ground for gardens and livestock,” Philippe said. “Back then we would play in the woods, we would pick berries.

“But we could see it changing every year. We could see the bayou getting wider, the woods dying, the marsh becoming open water. It was terrible.”

For a people whose spiritual life is tied to the land, watching those changes was like watching the slow death of family members.

“We don’t think of the land — the environment — the way you do,” Philippe said, referring to non-natives. “It isn’t made up different things, it is all one thing.

“And it isn’t part of our surroundings, it is part of us, essential to our life way. We can’t live without it.

“So when it is unhealthy or sick, so are we. And when you destroy it, you are destroying our life way.”

LAND RIGHTS AND WRONGS

For many coastal fishing villages, that destruction meant profits and wealth as they shifted to oil hubs for the growing industry. But it brought hardship to the people of Grand Bayou. They received no royalties from the minerals being extracted from the property they had lived on for centuries. Instead the levees and canals left behind were killing the means for their livelihoods and erasing the platform necessary for their cultural survival.

“They took the land and destroyed it — even while we lived on it,” Philippe said.

How tribe members lost the rights to the land they had occupied for hundreds of years is unclear. Unlike the tribes in other parts of North America, they did not go to war against the Europeans colonizing the continent or, later, with the United States. So there are no known treaties ceding land from one nation to another, as happened in those conflicts.

Attorney Joel Waltzer, who has represented other coastal tribes, said in many cases, the United States government transferred lands being used by natives to the new states once they were admitted to the union. Those lands were eventually sold to companies developing the oil and gas industry.

“It wasn’t until oil was discovered that outsiders became interested in getting the land around there,” he said. “And large landholding companies acquired very large tracts primarily for the mineral rights.

“The native people had no idea what that meant. They wanted the land for fishing, hunting and trapping. And they could continue to do that – at least while the wetlands lasted.”

Philippe said older members of the tribe remember when the land was officially taken. They said a delegation of state and local officials went home to home to have tribal members sign documents giving the land away.

“They recall their parents sitting at a table with someone from the state and parish with sheriff’s deputies also standing in these small rooms watching as the papers were given to them,” she said. “They were told they had no choice. It was eminent domain – the state had better uses for the land.

“In return, we were given ownership of about 300 feet of land on either side of the bayou. They got the rest –— thousands of acres.

“They told us it was no big deal because we could continue to hunt, fish and trap. But it was definitely coercive. They didn’t call the whole tribe together. They isolated each family and pressured them to sign, even though most of those people couldn’t read or speak English very well, or not at all.”

Indeed, the whole transaction may have been incomprehensible to the natives because they did not understand the concept of owning land.

“No one owned land in that sense. You couldn’t own land that way,” Philippe said. “The land was part of us, and we are part of the land. You can’t give yourself or your community.”

Philippe said the tribe had no documents to support those stories. They had no written language, instead preserving important events in oral histories passed down to each generation.

AN APPROACHING STORM

At first, the arrival of the dredges and drilling platforms made little difference to the tribe because the delta stayed healthy. But by the 1960s, the changes became apparent, and they were accelerating. Ponds were becoming lagoons, and lagoons becoming lakes. The forests on the ridges were dying as the land sank, and the cypress swamps were being killed by saltwater.

The vast, thick barrier of swamps and marshes that once stretched to the distant Gulf of Mexico not only provided sustenance, it helped protect homes and village from storm surge. As those wetlands turned to open water, storm damage to the village became unacceptable for some residents, and they began moving away.

Philippe said the population began declining seriously in 1965 after Hurricane Betsy destroyed most homes. On the eve of Hurricane Katrina only about 40 families remained in the village.

“Katrina destroyed what we rebuilt after Betsy, and we have only 14 families living here full time now,” Philippe said.

Grand Bayou today bears little resemblance to the village Philippe was raised in. The oak trees that once shaded the bayou banks are gone, as are the woods, fruit trees and berry bushes. The surrounding landscape is brackish marsh grass broken frequently by expanding ponds and lagoons. Grand Bayou is now 50 yards wide in most places, and eroding more each year. The residents now live in homes resting 15 feet above the marsh on wooden pilings to look down on the ruins of earlier homes slowly collapsing into the marsh.

Philippe estimates there are 40 regular residents of all ages. Most are commercial fishermen, but some work “on the outside” in schools, hospitals and even in the oil patch.

“We have to work outside because the land can’t provide for all of us anymore,” she said. “We could see this happening — everyone could. Nothing was done.”

TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE

Although the causes and cures for the crisis were well known by the 1970s, Louisiana did not develop a comprehensive plan to fight back until after Katrina. By then, many areas on the delta south of New Orleans had sunk too low or become too open to the Gulf to be included in the effort.

The state Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority has two overarching standards for projects: Build only wetlands that will withstand sea-level rise and subsidence, and build them in areas that will protect the greatest number of people.

Many land-building projects have been completed in Plaquemines Parish, and some of the largest, most expensive are scheduled for the decades ahead. But none is around Grand Bayou.

Tribe members want help from the coastal plan to adapt to live in the wetlands, even as conditions become worse.

One idea is to gradually transition from homes attached to the land to houseboats. That would allow them to literally haul the village into protective harbors when storms approach. One such houseboat barge is already in the village for a tryout, but the state didn’t have anything to do with it.

Other ideas include building floating gardens for vegetables, and even floating pens for some livestock.

But tribe members believe the development criteria for coastal master plan projects has not been responsive to their unique needs.

“We have participated in the process, gone to the public meetings, even gone to Baton Rouge to the offices, but they don’t really hear us,” she said.

The tribe members don’t dispute the long odds facing their future at this location, Philippe said. They have seen the projections showing the combination of subsidence and climate-change-driven sea level rise could result in this area being covered by 6 feet of the Gulf of Mexico by the end of the century. But even a move behind flood-protection levees would be too risky to cultural survival – and likely would not provide lasting protection.

“These levees are only temporary solutions – they’ll be knocked down by a storm, and the people relocated behind them will be wiped out or have to move again,” she said.

“And we can’t remain who we are if we move off the water. We are part of the land, just like the plants and wildlife and fish.

“If we leave that, it would mean the end of us.”

What the tribe really wants, she said, is for the companies and governments that destroyed their wetlands to rebuild them.

“That would be justice,” she said.

*Correction: This story originally misspelled Rosina Philippe’s name and the name of the Atakapas-Ishak/Chawasha tribe. (Feb. 8, 2017)