Louisianians spend most of their days worried about too much water. Rainstorms that flood homes. Hurricane surges that can wipe out communities. The Mississippi River so swollen with snowmelt, it laps at the tops of levees and threatens towns.

But there are times when not enough water can be a problem. Our spongy landscape contracts, levees crack and sink, roads buckle, water and gas lines break, lawns turn brown.

We’re in one those rare times right now. New Orleans just had one of its driest Octobers on record, according to the National Weather Service.

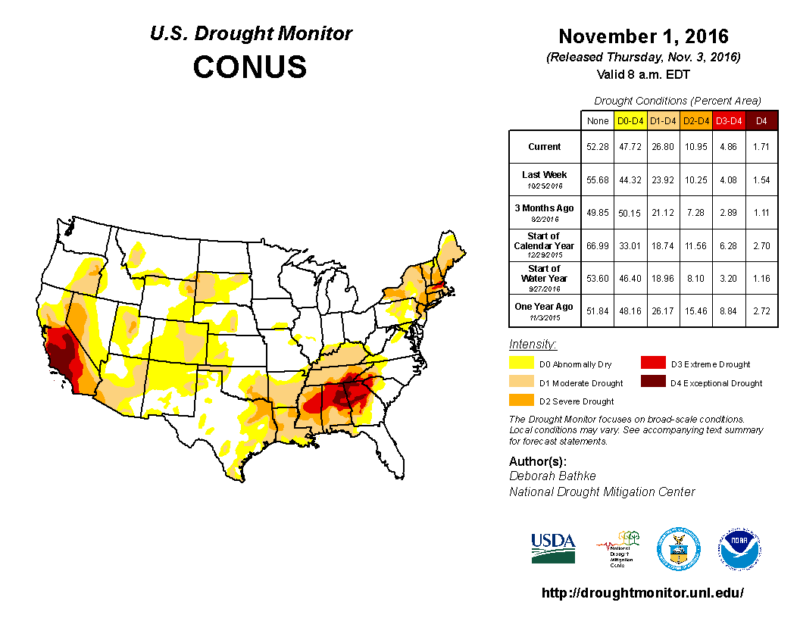

The National Drought Monitor says most of Louisiana is in the grip of the same drought squeezing much of the Deep South dry. And it might continue for weeks to come.

“Normally in October — our driest month — we see about 3.5 inches of rain, but this year we’ve had five-hundredths of an inch” at the New Orleans airport, said Kenneth Graham, Meteorologist-in-Charge for the New Orleans office of the National Weather Service.

“And looking at the global patterns and the monthly drought outlook, there isn’t much of a change expected.”

Swings between extreme events such as floods and droughts are part of the pattern that climate scientists have long predicted would occur due to global warming. Researchers concluded that intense, 1,000-year rainstorms like the ones that flooded Baton Rouge in August are 40 percent more likely due to climate change.

Officials in New Orleans say the dry weather is no cause for alarm yet.

The Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-East, charged with maintaining the levees around New Orleans, did not respond to requests for comment.

However, a spokesman for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which designed and built the levees, said cracking on their surface isn’t unusual and doesn’t threaten their integrity.

Corps spokesman Ricky Boyett said the agency is monitoring the development of a “saltwater wedge” in the Mississippi River. The river is deeper than the Gulf of Mexico where the two meet. When the river is low during dry months, the current slows and heavier saltwater pushes upstream. If the saltwater moves far enough upstream to threaten community water intakes, the corps will build a berm on the river bottom to block the wedge. That last happened in 2012.

Boyett said the wedge is not a threat now, remaining about 20 miles south of Venice at Head of Passes. But the river level is expected to drop further in the next couple weeks, which probably will allow the wedge to continue moving north.

Around New Orleans, homeowners can expect to see their lawns pulling away from slabs and piers, spidery cracks extending across plaster walls, and doors and windows that stick. Streets and sidewalks will shift as well.

It all happens as the soil dries and contracts. In some areas, the soil will swell when the rains return, said David Waggoner, a chief architect of the Urban Water Plan, which is designed to keep soils hydrated by storing some rainwater on the surface.

Those torrential rainfalls during the summer still have New Orleans and Louisiana wetter than normal for the year. Louisiana state climatologist Barry Keim said Louisiana is 7.87 inches above its average through October. The gauge at Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport has recorded 5.03 inches more than the normal through October.

“It’s really ironic,” Graham said. “A few weeks ago, I couldn’t mow my lawn because it was so saturated the lawn mower would sink. And now I’m worried about the grass dying.”