These are nervous times for some supporters of the RESTORE Act, the law that will divert 80 percent of the fines BP will pay for polluting the Gulf of Mexico from the federal purse to projects intended to restore the Gulf ecosystem and economy.

As they helped push the legislation through Congress, environmental groups backing the bill asked these questions:

Will the windfall that could reach $13.7 billion actually be spent on major initiatives serving the entire Gulf ecosystem?

Or will a feeding frenzy by state and federal agencies chew it up into small pieces for site-specific projects that have little overall effect?

The first projects under consideration are small and local.

Those handling the money said that’s just because the amount involved is relatively low, and they said even the little projects can form the basis for larger work to come. But environmentalists wary of government promises are uneasy and on guard.

“The real promise for RESTORE was that it could provide the funding for the big-ticket programs – Everglades restoration, Louisiana’s coast – that were languishing for lack of funding from Congress,” — David Muth, National Wildlife Federation

The Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council is the joint state-federal panel charged with overseeing RESTORE money. It is reviewing 50 proposals for the first wave of funding it can disburse, about $180 million. Most of those are site-specific projects.

That worries David Muth, director of the Gulf Restoration Program for the National Wildlife Federation, which helped then-Sen. Mary Landrieu craft the legislation and lobbied it through Congress.

“The real promise for RESTORE was that it could provide the funding for the big-ticket programs – Everglades restoration, Louisiana’s coast – that were languishing for lack of funding from Congress,” he said.

“I’m not saying any of these smaller projects are not valuable. But if they let this turn into a fight between five separate states and six separate federal agencies for pet projects, then we will have lost this one chance to address the Gulf as a whole.”

Muth is also concerned the call for project proposals violated one of the priorities listed in the Comprehensive Plan setting ground rules for selecting projects.

“The Council is supposed to give priority to proposals that fund existing projects, yet most of these proposals are new,” he said.

But Justin Ehrenwerth, executive director of the council, said those concerns are unwarranted.

The parameters for this first round of proposals were guided by the relatively small amount of funding available, he said. Since the $180 million could not fund the expensive efforts, proposals for smaller projects were acceptable.

“We’re expecting billions in (when the lawsuit is settled), but we had this money ready to go, so we decided rather than just let this sit while we waited for the billions, we should start getting some work done,” Ehrenwerth said.

Ehrenwerth said the five state and six federal agencies that have seats on the council were advised proposals solicited in August had to address habitat or water quality and would be evaluated on four criteria.

- They would be “foundational” – meaning they were laying the groundwork to address larger goals once more funding was available.

- They could be “leveraged” – used in conjunction with or attached to other projects proposed by other agencies.

- They could be “sustainable” – their results could stand up over time.

- That had a high probability of success.

The 50 proposals – five from each council member – include 380 subcomponents, Ehrenwerth said.

“We’re going through each of these subcomponents to see if they may fit in with other proposals,” he said. “That’s one way to leverage these things.”

The proposals carry funding requests that add up to $780 million, more than four times what’s available. Ehrenwerth hopes to have a list of finalists presented at a series of public meetings during the summer. The final selection should happen before the end of the year.

If the other four Gulf states were not offered equal shares in exchange for their support the bill would have failed – and the fines would have followed their usual path to the federal purse.

Denise Reed, chief scientist at The Water Institute of the Gulf, said that process will be closely watched by those who hoped the RESTORE Act windfall would help fund big projects, such as Louisiana’ $50 billion Master Plan for the Coast. She understands how the current tight funding shaped this first call for projects, but she believes the final picks could reveal how the council will make decisions in the future.

“I think the crux of the matter is going to be how they determine what ‘foundational’ means,” she said.

Some of the proposals clearly will not score highly on the four criteria for selection. For example, the Army Corps of Engineers has submitted a proposal to restore and create 640 acres of wetlands on the Bird’s Foot Delta at the end of the Mississippi River at a cost of $36 million. Yet Louisiana has not included any projects on that delta in its Master Plan because its subsidence rate of five feet per century will put it under water before 2100.

“If we had a stronger comprehensive plan, proposals like this might not even be made,” said Muth. “We need clear guidelines that match the overarching purpose of RESTORE, which is to address the ecosystem-wide problems we face. That’s why we supported RESTORE.”

For some Louisiana coastal advocates, support for RESTORE was simply a matter of “something is better than nothing.” Although the Bayou State suffered the vast majority of pollution damage from the Deepwater Horizon, if the other four Gulf states were not offered equal shares in exchange for their support the bill would have failed – and the fines would have followed their usual path to the federal purse.

Environmental groups pushed for the bill to address broad environmental issues. But with billions at stake, each state’s congressional delegation was busy trying to shape the rules to favor their own coastal environments, communities, agencies and businesses.

That political reality is clear in three of the bill’s primary features:

- It established the 11-member council with representatives of the five states and six federal agencies each having equal votes on most spending and project selection decisions.

- It required a comprehensive plan to set out priorities for selecting projects.

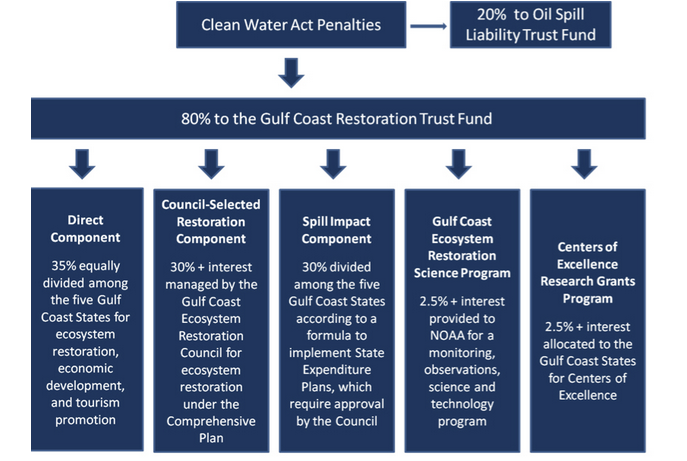

- The fines will be divided into to five different accounts – or “pots” – each with its own spending rules.

Pot 1, called the Direct Component, is the big payoff to other states for their cooperation. It divides 35 percent of the fines equally among the states, which can use it for “ecosystem restoration, economic development or tourism promotion.” While the projects must fit into one of 12 activities outlined in the law, they are very broad – and there will be very little federal involvement. States likely will spend the money within their borders.

Pot 3, the Spill Impact Component, reserves 30 percent of the fines for the council to select projects that can benefit a state’s economy as well as its environment.

Pot 4 gives 2.5 percent the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which said it will be used on 10 long-term projects recently announced by the federal government. And Pot 5 gets the same share to help each state set up a center for research on Gulf issues.

The current concerns center on Pot 2, the Council-Selected Restoration Component which will receive 30 percent of the fines for ecosystem restoration projects.

Projects for this pot must be selected based on guidelines in the Initial Comprehensive Plan. But since they can take place anywhere along the Gulf and will be chosen by a vote of the Council, this is where a lot of internal politics will take place.

Muth and others in the green community are concerned the comprehensive plan is not strong enough to prevent parochial interests from sapping the impact of Pot 2.

“It is our position that there are priorities set down in the comprehensive plan, and they should be followed, but that they were not in this case,” he said.

“There’s a potential for states getting together to support each other for their own pet projects,” he said. “Well, Pot 1 is there for states to address local priorities. Pot 2 should be used for the larger, big-ticket items.

“We’re concerned this round of spending could set the wrong precedent.”

Ehrenwerth says critics are reading too much into this initial effort, that the priorities of the comprehensive plan will be followed.

Reed is reserving judgment.

“They say the proof is in the pudding,” she said, “and that may be the case here.”