If a hurricane enters the Gulf this year emergency planners and private citizens will have access to a new Website and system of maps the National Hurricane Center developed to alert coastal communities of the risks heading their way.

But local authorities say it should come with this warning: Use with caution.

Chris Guilbeaux, a state emergency official, said the system will be “basically meaningless” to him during a major storm because the most reliable maps can not be issued until long after he must order evacuations.

And Shirley Laska, a UNO researcher who is expert on the risks facing communities on Louisiana’s sinking, crumbling coast worries some of the maps could inadvertently give residents a false sense of security

“My concern is that if people who are not Internet savvy and don’t know how to use these new maps, they could be led to believe they’re safe, when they actually aren’t,” Laska said.

Her worry surfaced after she discovered different maps for a major Category 3 storm depicting different outcomes in the metro area.

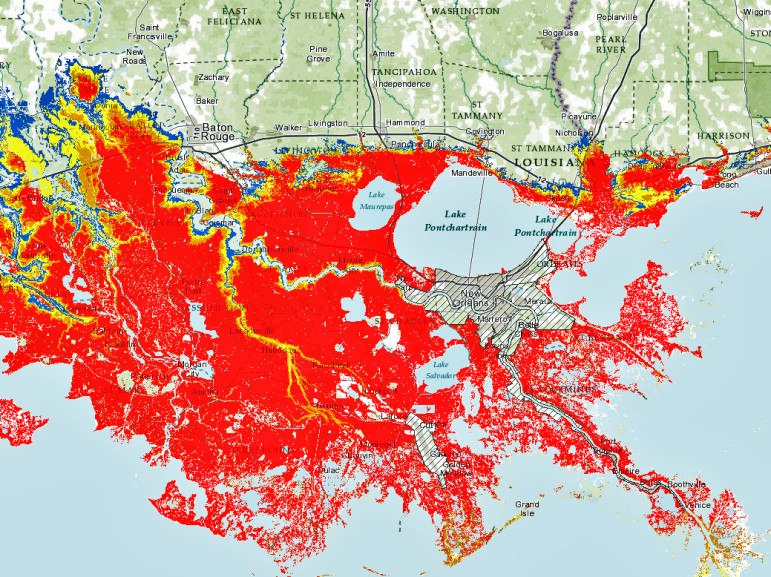

On the National Storm Surge Risk Website, a sea of red inundates almost everything in southeast Louisiana from north of Baton Rouge to Grand Isle – except the area inside the new, $14.5-billion levee system protecting the New Orleans area. That area is colored in the less alarming pattern of white with thin black lines. It looks dry.

But in other maps that will be used for the same storm, area inside the new levees is also awash in red.

But a careful reading of the maps shows shows that white-with-stripe pattern doesn’t not signify safety. The map legend for that pattern advises readers: Consult Local Officials For Flood Risk.

No city of New Orleans officials responded to The Lens’ request for this critical information.

We did get a quick answer from Guilbeaux, deputy director in the Governor’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness: No one should feel safe inside the levees as a worst-case Cat 3 storm approaches. They should be long gone.

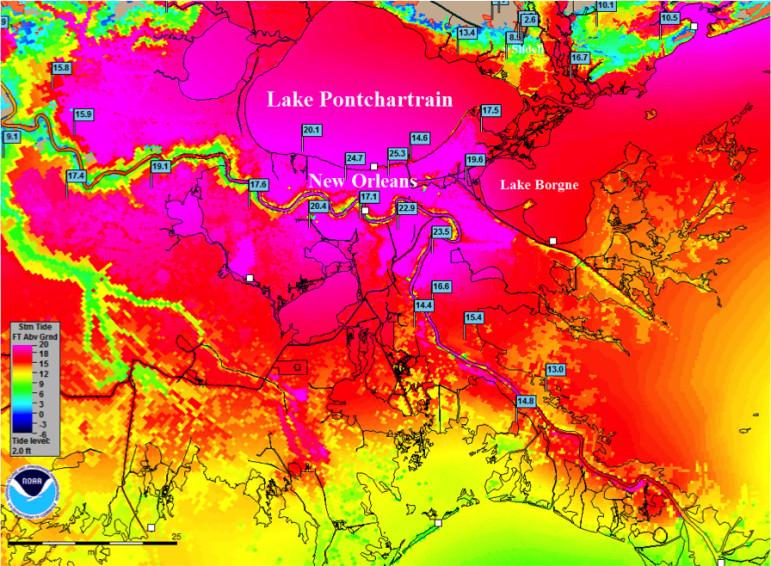

In fact, Guilbeaux said his office would order Orleans and Jefferson parishes evacuated 96 hours in advance of such a storm making landfall. That decision is based on other maps from the hurricane center showing the surge from that worse-case scenario reaching 25 feet, easily overtopping most of the new system, which was built to repel a lesser storm.

So why doesn’t the hurricane center paint the metro area red in all of its maps forecasting such high storm surge?

“The science has moved forward a great deal, but we still don’t have the tools that can provide a high level of confidence when predicting what will happen inside those levees,” said Ken Graham, Meteorologist-in-Charge of the New Orleans-Baton Rouge office.

That confidence level is the key to some of the confusion.

Despite great advances in seeing and measuring what weather is doing in real time — and understanding why that is happening — meteorologists still can’t nail down exactly when and where those events will occur. So many variables are important to each outcome, even daily forecasts carry caveats on accuracy.

The job doesn’t get any easier forecasting hurricane storm surge, when the cost of inaccuracy might be measured in lives.

The height of storm surge can be influenced by the sheer size of the storm, its barometric pressure, its speed, the surface temperature and depth of the water, the angle at which the storm strikes the coast, the bottom contours of the water body, the types of soil and surface features of the land it strikes — to name a few.

A shift in any of those variables at any time could change the computer program results, and while the storm is over open water many of those variables are in play. This doesn’t even include wider weather patterns outside the storm that could dramatically change its course, moving it completely away from southeast Louisiana.

All of that means confidence in predictions many days away are low.

Playing it safe with forecast

But because emergency officials want as much advance time as possible to act, the hurricane center has produced models – what it calls “products” – that estimate a range of outcomes based on changing menus of those variables far in advance of landfall.

The Maximum of Maximums predicts surge for various category storms when the contributing factors are at their most intense.

The Maximum Envelopment of Water shows the greatest extent of storm surge, but only by storms approaching from the same general direction.

Each of those can show the metro area inside the new levee system flooded because it is using simple math: If the surge is 20 feet and the levee is 15 feet, inundation will occur.

But the confidence level of those products is not high.

As the storm moves closer, the hurricane center stamps its advisories and forecasts with a higher level of confidence, eventually reaching 90 percent.

This includes the product called P-surge, short for “Potential Storm Surge Flooding Map (Inundation)” which is issued when landfall is less than 48 hours away.

It’s at this point the red of inundation disappears inside the new levees and the white-with-stripes patterns occurs.

“Sure, if the models say surge is going to be 20 feet and the levee is only 15 feet high, we’re pretty confident water is going to go over the top,” Graham said.

“But we don’t have the tools to say with that 90-percent confidence level how much, for how long, and how deep the water will be across different parts of the area inside those levees.

“We’d like to, but we just can’t yet.”

Don’t just read maps — listen to emergency officials

Guildbeaux said the his office notified New Orleans officials about the state’s concerns that the maps might cause a false sense of security for people inside the levee system.

But Guilbeaux said those concerns should be a moot point for emergency planners in the region because the new map system is “basically meaningless” to residents of southeast Louisiana. Not because the project is flawed, but because this region’s landscape and demographics demand a longer lead time to evacuate than other coasts in hurricane country.

“The map showing storm surge with high confidence level comes out after the storm is within 48 hours of the coast,” he pointed out. “That might be plenty of time for people living in Florida or North Carolina or Alabama because they just have to drive 10 or 15 miles to be safe.

“But down here, you might have to drive 100 miles to find high ground where you can be safe from the surge.

“We love the product, but we told them, if they can’t produce it at 96 hours out with high confidence, then it doesn’t help us much.”

Another challenge in southeast Louisiana is actually getting those people out. Many have no transportation.

“We have to provide transportation for a lot of people living in Jefferson and Orleans, and that means getting enough buses and getting them down there,” Guilbeaux said. “And guess what? We don’t have enough buses in Louisiana to do the job. That means we have to get them from neighboring states, and get them down there.

“So, you see, telling me what’s going to happen in 48 hours is basically meaningless to us. By then, we’ve already ordered an evacuation – and we’ll live with the consequences.”

Graham understands concerns about confusion expressed by Laska and others, and offers this advice.

“First, while it’s true a picture’s worth a thousand words it’s also true these pictures may need a lot of words to fully explain them,” he said. “The idea of this project is to provide a product that will help people – especially the officials – understand the risk they’re in. But we have to make sure they understand what they’re seeing, what these maps are telling them.”

His second suggestion: No one should use the maps and ignore the local officials.

“Those are the people who will keep you safe. It’s their job,” he said. “If they tell you to leave – leave.”