In 2000, someone shot a young man in a Slidell club. Investigators quickly zeroed in on McKinley Phipps Jr., a rising star in New Orleans’ rap scene. He was convicted of manslaughter. But witnesses have raised questions about the key eyewitness, and one woman says she was coerced into pointing the finger at Phipps.

A shot in the dark can launch a music career. In the case of an up-and-coming rapper, it ended one.

In February 2000, McKinley Phipps Jr., a rising star in New Orleans’ rap scene, attended an open-mic night at Club Mercedes in Slidell, La. A fight broke out. Someone shot and killed 19-year-old Barron Victor Jr.

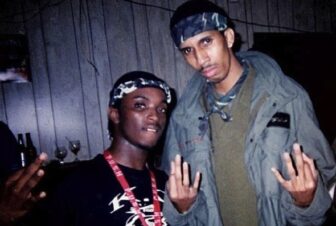

Phipps, there to sign autographs and meet fans, didn’t have a criminal record. But he was learning to play the part as a gangsta rapper nicknamed “Mac the Camouflage Assassin,” signed to Master P’s No Limit Records.

Deputies quickly zeroed in on Phipps after witnesses said they saw him with a gun. He was arrested hours after the shooting.

The next year, he was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 30 years in prison, abruptly ending his career at 24. He has maintained his innocence throughout.

A three-month investigation by The Medill Justice Project, in partnership with The Lens and Louisiana State University, has revealed some evidence that supports Phipps’ claim:

- Two people at the club that night later questioned whether the key eyewitness who testified against Phipps saw the shooting.

- The only other eyewitness to testify against Phipps backed off her claim of seeing him fire his gun. She said she had gone back to the St. Tammany Sheriff’s Office to recant her statement, but the prosecutor said during the trial he had no knowledge of her doing so. Last year, she signed an affidavit saying she had been coerced into accusing Phipps.

- Other witnesses gave conflicting accounts to authorities. Some said Phipps didn’t fire a shot.

- Someone else confessed to the shooting, but investigators didn’t believe him.

Russell Baker said he was standing next to Phipps when the shots were fired. “I know he didn’t do it,” Baker told The Medill Justice Project earlier this year, sitting at a table in a coffee shop. “As close as I am to this table is where I was with him that night.”

Baker wasn’t called to testify at Phipps’ trial.

New Orleans private investigator Miguel Nunez has been looking into the case at no cost because he believes Phipps is innocent.

Phipps’ case, he said, is a “classic example of … things are not what they always appear.”

Fight breaks out on a crowded dance floor

Phipps, whose parents organized the open-mic event that Sunday through their production company, went to see the performers from Slidell and New Orleans and to meet fans. His father collected money at the door. Patrons were searched for weapons as they entered, although performers and some of their friends came in the back.

The bar was crowded, smoky and dark, witnesses said. After midnight, a large fight broke out near the stage. Witnesses told investigators they couldn’t make out who exactly was involved.

Accounts differ on whether Phipps was involved in the fight. One or two shots rang out — accounts vary — and people scattered. Victor ran to the front of the club and collapsed near the door.

“From the time the shots went off, everybody started screaming, ‘Mac shot him, Mac shot him,’” Yulon James testified at the trial, referring to Phipps.

Phipps was arrested at his home in Baton Rouge at about 4 a.m., just hours after the shooting.

Later that day, a woman who was at the club that night came forward to say that deputies had arrested the wrong person. She and two friends, none of whom knew Phipps personally, said they were standing near the fight. They told authorities they saw a man matching Phipps’ description wave a gun and ask who was shooting as he ran out of the club.

One of them, James Barney, said he saw Phipps pull the gun out as people ran from the shooting.

When Phipps talked to deputies, however, he told them he had a gun in his truck, but not in the club. Asked why people would have said he was the gunman, he suggested it was just because he was well-known.

Deputies seized several guns from Phipps’ house and SUV, including a .38 caliber revolver, a 9 mm handgun and two semiautomatic rifles. None of the guns matched the bullet that killed Victor. The murder weapon was never recovered, and no physical evidence tied Phipps to the crime.

Investigators got another lead in the first 24 hours. A lawyer for No Limit Records came to the St. Tammany Sheriff’s Office in Slidell and said a man named Thomas Williams had shot Victor. The lawyer provided names of people in New Orleans who would corroborate that information.

Nine days later, Williams showed up at the St. Tammany Sheriff’s Office with his minister. Williams, who worked as a security guard for Phipps, said he had broken up the fight and was walking away when a man charged at him with a broken beer bottle.

“And the next thing I realize, I reached and I fired,” he said. “And I panicked, I was nervous. I didn’t know what else to do. I was protecting myself, trying to, ya know, protect myself. He was coming towards me to hurt me.”

Baker told deputies that Williams, the security guard, had told him he fired his gun that night, though he didn’t say he had shot Victor.

At trial, a detective and an expert witness testified that Williams’ confession didn’t match the evidence. Williams told deputies he was about 10 feet away when he fired the gun, but the wound showed soot marks indicating a close-range shot. The prosecutor pointed out that no one else said anything about a broken bottle. And Williams couldn’t describe his gun, which he said he had owned for about a month.

Williams declined to comment for this story.

Relative of victim was key eyewitness

The case against Phipps largely hinged on the eyewitness testimony of the victim’s cousin, Nathaniel Tillison.

Tillison testified that Victor’s friend got in a fight and fell to the ground after being hit in the head. Phipps’ entourage was kicking Victor’s friend, he said, when Victor stepped over the man to shield him.

Phipps, Tillison said, held the gun inches from Victor and pulled the trigger. Tillison said he and Victor ran toward the front door, where Victor collapsed.

Asked by the prosecutor how he knew Phipps had done it, Tillison responded, “Because I looked dead in his eyes to see him.”

But statements by others at the scene call into question whether he saw the shooting.

Joselyn Hill, a bartender at the club that night, told The Medill Justice Project that after the shooting she saw a man, whom she believed was related to Victor, shout profanities and throw chairs when he found out his cousin had been shot.

That’s consistent with what McKinley Phipps Sr., Phipps’ father, has said. He testified that someone — though he didn’t name Tillison — walked into the club, saw Victor on the ground, cried out something about his cousin and started to throw bottles and chairs.

This year, Phipps Sr. told The Medill Justice Project that Tillison appeared surprised when he walked in the front door and found his cousin on the floor, shot. Phipps Sr. said Tillison began throwing chairs and shouting.

“I don’t even think he was in the bar when the guy got shot,” Phipps Sr. said. “Because he was so surprised.”

In the days after the shooting, deputies went back to Tillison to clear up inconsistencies in what he had told them. He ended up sitting down with investigators three times. He initially said someone with Phipps had hit his friend in the head; later he said it was Phipps. On the witness stand, he said he was sure Phipps wasn’t the one who struck his friend.

Tillison also told an investigator that he saw two people with guns, including someone he identified as a bodyguard. At one point, Tillison told the deputy, “Now Mac say anything, if Mac didn’t do the shooting, you know who did.”

Throughout the questioning by investigators and lawyers, however, Tillison was otherwise steadfast that Phipps had shot Victor.

Tillison did not respond to repeated requests for comment, nor did Victor’s family or prosecutors.

Other witness claims she was coerced

The only other eyewitness at trial was Yulon James, the girlfriend of Phipps’ promoter. She gave conflicting testimony. Hours after the shooting, she gave a statement that appears to indicate that she was sitting at the bar next to Victor when she saw Phipps shoot and Victor drop to the floor.

dc.embed.load(‘http://www.documentcloud.org/search/embed/’, { q: “document: 1383804 document: 1383543 document: 1382032 document: 1382030 document: 1375096 document: 1375091 document: 1375088 document: 1375084 document: 1375081 document: 1183855”, container: “#DC-search-document-1383804-document-1383543-document-1382032-document-1382030-document-1375096-document-1375091-document-1375088-document-1375084-document-1375081-document-1183855”, title: “Read the documents cited in this story”, order: “title”, per_page: 3, search_bar: true, organization: 146 });

During the trial, James said she glanced over at the fight and saw sparks leaving a gun in Phipps’ hand. Jason Williams, a lawyer for Phipps and now a New Orleans city councilman, asked her why she had told deputies that Victor was sitting on a bar stool. She said she meant that she saw him on a bar stool and the next time she saw him, he was on the floor.

Williams asked her, “Ma’am, in all actuality you really couldn’t clearly see what happened when shots were fired in that bar, could you?”

James responded, “Not directly, no, and I told them that later, you know.”

She went on to testify that she had returned to the Sheriff’s Office and had spoken with different detectives than the first time.

Lawyers on both sides said this was news to them. The judge took the unusual step of having the prosecutor ask the detectives if they knew anything about this second statement. The prosecutor said at trial the detectives said they didn’t, and they would have included it in a report if they had.

James reiterated her claim of a second statement in a May 2013 affidavit obtained by Nunez and never publicly disclosed before. In it, she said that law enforcement officials coerced her into pointing the finger at Phipps.

The next day, she said in the affidavit, she went to the St. Tammany Sheriff’s Office to “correct my statement.” She said, “I, in fact, could not see who shot Barron C. Victor Jr. when I heard the shots being fired inside ‘Club Mercedes’ the night of the incident.”

James declined to comment for this article. Law enforcement officials did not respond to requests for an interview.

Records and interviews also reveal several other eyewitnesses, including Phipps’ friend Baker, told authorities Phipps didn’t fire a shot at the victim. None was called to testify.

Eyewitness accounts questioned

Recent studies have shown eyewitness testimony can be unreliable. Gary Wells, a professor of psychology at Iowa State University and one of the world’s foremost experts on the reliability of eyewitness testimony, said certain factors may compromise people’s memories.

Told of James’ conflicting statements, Wells said she was an “unreliable witness.”

“I think we have to take very seriously her claim that she tried to recant her initial statement within 24 hours and that she felt intimidated,” he said, “and that apparently there were not good records made of that, which is consistent with the idea that nobody really wanted to hear what she had to say in the recantation.”

Wells said the buzz through the crowd that “Mac shot him” could have shaped James’ recollection of what happened.

“That’s how the contagion floats around,” he said. “That’s how you can get potentially a witness who didn’t see much of anything, but maybe sees a flash or whatever, immediately starting to fill in the gap, putting his face and putting him into that scene.”

Lyrics on trial

Rap lyrics used against Phipps

At trial, Assistant District Attorney Bruce Dearing used Phipps’ lyrics and his nickname “Mac the Camouflage Assassin” to help portray Phipps as a violent person capable of murder. He recited lyrics from the song “Murda, Murda, Kill Kill” and told the jury that Phipps “chose to live those words.”

As an artist signed to a label that specialized in gangsta rap, Phipps released songs that explored struggles of urban life, including crime and street shootings. Several experts said rap lyrics should not be interpreted as autobiographical statements.

Gangsta rap “is by definition centered around graphic depictions of violence,” said Erik Nielson, a professor at the University of Richmond. “Rap lyrics are not representations of the person. This is a distinction that we don’t have trouble making with any other fictional form.”

This issue came up numerous times in the trial, with Phipps’ attorneys objecting to the prosecutor’s continued references to Phipps’ lyrics.

“None of them … described what happened in that club,” Williams, Phipps’ attorney, said in an interview this year. “None of them were describing some accurate, violent event that McKinley was involved in… it was art.”

Phipps was charged with second-degree murder, but the judge told the jurors they had the option to convict him of the lesser charge of manslaughter if they believed “the killing [was] committed in a sudden passion or heat of blood.” Second-degree murder carried a sentence of life in prison; manslaughter carried a maximum sentence of 40 years.

After about six hours of deliberation, jurors asked for clarification on the difference between the two charges. An hour later, they convicted Phipps of manslaughter. A conviction required 10 of the 12 jurors to agree; two disagreed with the verdict.

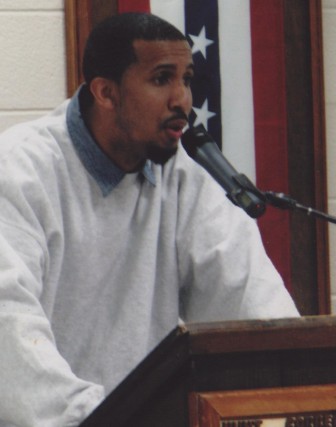

Phipps is serving his sentence at Elayn Hunt Correctional Center in St. Gabriel. He’s scheduled to be released in 2024 based on sentencing laws. He performs in prison and occasionally writes songs.

He has been unsuccessful in appealing his conviction.

“I did not kill [Victor],” Phipps, 37, said in a recent telephone interview from prison. “And I just hope that someday that I can prove to this young man’s family that I didn’t take his life.”

This story was reported by The Medill Justice Project at Northwestern University. Contributors include students Dan Barlava, Jessica Bickel-Barlow, Cheyenne Blount, Rachel Janik, Alexandria Johnson, Maggie Kadifa, Cindy Li, Tade Mengesha, Zaynab Quadri and Lissette Rodriguez; Alec Klein, professor and director; and Amanda Westrich, research associate. Contributors from Louisiana State University include students Zach Carline, Spencer Hutchinson and Wilborn Nobles, and professor Jay Shelledy.