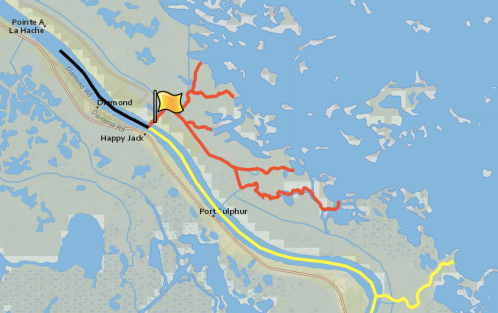

When the Mississippi River broke through its east bank south of Pointe à la Hache on Mardi Gras two years ago, a spirited debate broke out: Was the new opening simply a temporary breach or a natural pass?

Some coastal advocates have called it a “pass,” urging the state to allow it to grow unabated so it can help rebuild the adjacent sinking wetlands.

Some state officials have been more circumspect. They’ve called the opening a breach and listened to the pleas of an energy company that wants to have it controlled because it impedes access to its oil and gas wells.

Now the state Department of Transportation and Development is preparing to weigh in on the side of the “pass” advocates. It is readying a request to the U. S. Board on Geographic Names to formally designate the opening “Mardi Gras Pass.”

The agency’s Geospatial Services Divisions has prepared an online “story map” that lays out in seven parts the history of the opening as well as hydrological data for its permanent name status.

The pass, according to the map, “is the first distributary to develop in the river’s delta in many decades.”

John Lopez, executive director of the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation, which has led the effort to keep the pass open, was not surprised by the Department of Transportation initiative.

“Back in March, the Coast Guard officially listed Mardi Gras Pass as a navigable waterway, so getting it placed on the maps just makes sense,” he said.

Officially getting a name may not end the debate between Lopez’s organization and Sundown Energy over how to manage the opening. When the breach occurred, it wiped out a road the company used to access several wells.

Sundown was granted a permit by the state Department of Natural Resources to build a bridge over the opening, but the foundation believes the culverts would be too small to allow the new waterway to reach its land-building potential.

“Nothing is really settled yet,” Lopez said. “We’re still hopeful the bridge, when it’s built, will be large enough and high enough to let Mardi Gras Pass reach its full capacity.”

And by then, it might have an official name.