Even before Hurricane Katrina, scientists had established that the soil across New Orleans was laced with an alarming amount of lead, which can cause a range of health problems, particularly in children.

The 2005 failure of the federal levee system then sloshed a nasty stew across the city leaving behind a new layer of danger in the form of elevated levels of arsenic, a known carcinogen.

Environmentalists who understood these dangers were excited in 2007 when the community endorsed a wish-list plan to spend $30 million in federal recovery money to address the problem of heavy metals citywide.

That excitement was somewhat lowered by the reality of city officials eventually setting aside only $4 million in federal disaster money to spend on the problem. That’s not even 1 percent of the recovery money made available by the Housing and Urban Development Department to execute the overall $411 million recovery plan devised largely through citizen input.

Now those advocates have descended well past excitement and solidly into frustration because $3.5 million of that has been tied up in a Byzantine city-state-federal approval process for more than a year, and the balance is still in the planning stage.

That leaves environmentalists frustrated – and worried for the health of the city’s youngest residents who frequent contaminated playgrounds and schoolyards.

“I think it’s important that the city secures that funding,” says Miriam Rotkin-Ellman, chief author of a recent study that showed new deposits of arsenic in New Orleans soil since the storms. “It is the key to securing the public’s health, particularly children’s health.”

Beverly Wright, president of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, was instrumental in preparing the pending request for the $3.5 million, starting in 2008.

But several formidable layers of bureaucracy stand between Wright and the money. Here’s how the process works for the overall $411 million available in recovery money from HUD:

- The City of New Orleans puts together project descriptions based off the goals laid out in the recovery plan approved by HUD. That plan was put together from pieces of the Unified New Orleans Plan, as well as parts of other recovery planning efforts organized by former Recovery Czar Ed Blakely. Each project description is submitted to the state for approval.

- Once the project description is approved, the city works with a private consult, Louisiana Solutions LLC, which was hired by the state’s Office of Community Development to ensure that grants meet HUD guidelines. While under Louisiana Solutions’ review, the application could go back and forth between it and the city several times before Louisiana Solutions is satisfied that it is ready to be submitted to the state.

- The Office of Community Development looks over the grant request, often with staff members from the Louisiana Recovery Authority. They can send it back to the city with more questions, or they make the final approval. This office regularly handles HUD grants and is familiar with the procedures required by Washington.

According to Christina Stephens, spokeswoman for Louisiana Recovery Authority, Louisiana Solutions first got a project description on the soil remediation program in August of 2008. An application was submitted to the state the following month but was sent back for more budget and implementation information, she said.

The city sent a second version to Louisiana Solutions in January of 2009, and the state approved the project description in April.

The project then went into a more intensive review process between the city and Louisiana Solutions between April and September, with discussions over budgeting, program guidelines and job descriptions. An application was submitted to the Office of Community Development in September, but it was sent back to the city with additional questions.

Another application was finally sent on December 23 to Community Development, which still has the application, and still has more questions to be answered, though they have not rejected the project.

“I believe the lead watch project is in the very final steps of being approved,” Stephens said this week.

Louisiana Solutions’ part in all of this is to make it “sellable” for HUD purposes, according to one of its managers Dan Gerrity who is currently based in Philadelphia.

Wright’s Deep South Center tested and cleaned soil in certain parts of eastern New Orleans in the first couple years after Katrina under its “A Safe Way Back Home” program, which was implemented in partnership with U.S. Steelworkers. For that, they used private donations and foundation dollars.

Her work with Howard Mielke at Xavier University in the 1990s unearthed the first soil samples showing hazardous lead levels throughout the city. Those samples were used as a baseline in the 18 months following the Katrina to test for new toxicity.

The new testing was done by Xavier, Tulane and Dillard universities and the Natural Resources Defense Council, the results of which were released in the January 2010 issue of the journal Environmental Research.

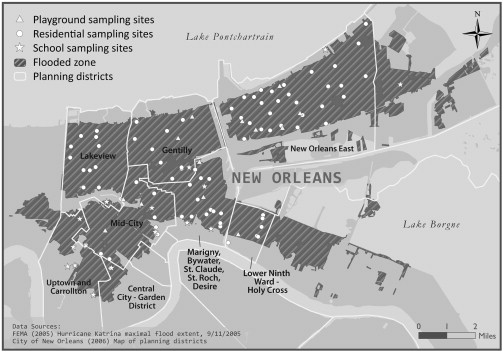

A recent alert for New Orleans was sent out by the Defense Council announcing that six schools and two playgrounds in Mid-City, St. Claude, Gentilly and the Carrollton neighborhoods had arsenic levels exceeding guidelines set by the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality. Health risks associated with this exposure are still being determined, but scientists have found that exposure to arsenic is linked to cases of certain cancers, cardiovascular diseases, skin abnormalities, neurological disorders and anemia.

“Children are more sensitive to arsenic contamination than adults because they play in the dirt, and are more likely to put their hands in their mouth, so they’re at greater risk from the contaminants in the soils,” the Defense Council’s Rotkin-Ellman said. “It’s important for kids to wash their hands especially in areas where there are known contaminants, but the soil really needs to be removed, and clean soil needs to be put in place.”