A new report finds that New Orleans schools spend more on administration and less on teaching than than they would have if they had not undergone a transformation to charter schools after Hurricane Katrina.

The research undercuts one argument for charters — that they’re a solution to bloated bureaucracies at parishwide school systems. However, prior research by the same group has concluded that New Orleans’ shift to charters has raised academic performance.

“If you decentralize an entire district, there’s a loss in economies of scale.”—Christian Buerger, Education Research Alliance

The findings come in a study released today by the Education Research Alliance for New Orleans. The goal of the study was to assess how school spending patterns have been affected by the city’s shift to charter schools after Hurricane Katrina.

Overall, New Orleans schools — the vast majority of which are charters — spent $1,358 more per pupil on operating expenses, or 13 percent, than a control group in the 2013-14 school year.

Put another way, schools spent that much more than they would have if New Orleans had remained a traditional school district after the storm.

Administrative spending increased $699 per student, or 66 percent, compared to the control group. Meanwhile, instructional spending dropped by $706 per student, or about 10 percent.

Doug Harris, director of the Education Research Alliance and one of the authors of the study, said the shift in spending wasn’t unexpected, but “the size of it was a little bit surprising.”

Christian Buerger, a postdoctoral fellow who worked with Harris on the study, said charter advocates often believe “that traditional school districts spend too much, have too much red tape.”

Their research found the opposite: “We find that charter schools spend even more in that area,” they wrote.

“If you decentralize an entire district, there’s a loss in economies of scale,” Buerger said. That can “lead to an increase in transaction costs.”

For example, parishwide school districts often employ a speech therapist to provide special education for some students. A staffer could have a full schedule by rotating among schools in the district.

A charter management organization, with a smaller enrollment, may not have enough demand for a full-time speech therapist. The charter network could hire a contractor, which often costs more per service hour. But the charter network would still need one of its employees to ensure that students are getting the legally required special education.

How the study was conductedAfter Hurricane Katrina, the state seized control of most of the schools in New Orleans. The state Recovery School District turned those schools over to charter operators, which operate independently and set their own educational priorities. Meanwhile, the local school board has approved several new charters.Charter schools now dominate the educational system in New Orleans, with just a handful of traditional, direct-run schools. Those, too, may soon become charter schools.To assess how that shift affected school spending, two researchers with the Education Research Alliance tracked per-pupil spending in New Orleans schools from 2000 to 2014. They focused on instructional and operational expenses to get a picture of the day-to-day costs of running a school.They also tracked spending at 17 school districts across Louisiana that were affected by Hurricane Katrina but didn’t undergo a similar transformation to charters. They used those districts to create a control group — essentially, a version of New Orleans in which there was not a shift to charter schools after the storm.Per-pupil spending in New Orleans and the control group was practically the same before the storm, showing the control group was representative of schools in the city. After the storm, they diverged.The researchers studied the difference in spending after Katrina between New Orleans and the control group to assess the impact of the charter movement.The Education Research Alliance is uniquely situated to study the charter movement because New Orleans has the highest percentage of public school students enrolled in charter schools in the nation.In a 2015 study, the Education Research Alliance found 25 of 30 school leaders surveyed reacted to competition by engaging in marketing strategies. Researchers had hypothesized they would spend more on improving academic outcomes.

As Harris put it, “it’s always cheaper to buy in bulk.”

One New Orleans charter school decided to give up its charter so its students could enjoy the advantages of a larger network. In 2015, the board of McDonogh City Park Academy voted to close it so ReNEW Schools could take it over.

Harris and Buerger found that New Orleans schools spend more on contracted services than the control group.

International School of Louisiana provides an example. In 2014, the school hired a contractor to get its books in order after it had trouble moving to a new payroll vendor. Later, its finance director quit.

At first, the school paid the contractor $14,000 per 10-day period for three workers, though it later cut the cost to $1,000 a week for someone to review the school’s finances weekly.

In addition to lacking economies of scale, Harris and Buerger said charter schools in New Orleans may spend more on administration because they need to provide more training and coaching for their younger workforce.

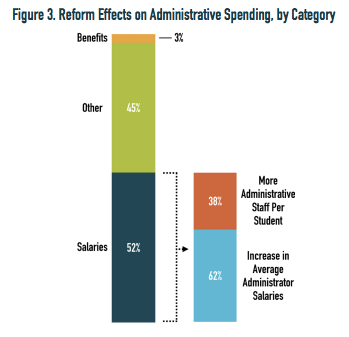

About half of the increase in administrative costs is due to a rise in in salary expenses. Administrators are being paid more, and there are more of them, Harris and Buerger wrote.

Charter school CEO salaries have long been a topic of discussion in the city. Last spring, NOLA.com/The Times-Picayune reported that the highest paid charter executive earned $262,000 in 2014.

Orleans Parish schools Superintendent Henderson Lewis Jr. earns $180,000 to oversee five traditional public schools and 22 charter schools. He recently announced those five schools will likely become charter schools as well.

However, the additional costs appear to come with academic gains. Harris and Buerger note their findings follow research that shows academics have improved since the charter transformation.

The report notes that even if the reforms are judged positively, it’s not clear that they are financially sustainable.

Teachers are paid less, have less generous benefits

The drop in instructional expenses — $706 per student — is due mainly to lower salaries and reduced benefits for instructional staff, Harris and Buerger found.

“I don’t think I anticipated that there’d actually be a decline in instructional spending,” Harris said.

After Katrina, with school canceled for the academic year, public school teachers were placed on disaster leave. The Orleans Parish school district couldn’t collect state funding because it didn’t have any students enrolled. So it fired more than 7,000 educators and didn’t renew their collective bargaining agreement.

Now, just a couple schools in the city are unionized.

When schools reopened, many started to hire more teachers through Teach for America and other alternative certification programs. Teach for America members often sign up straight out of college and commit to teaching for two years. The younger workforce has been a point of contention in the city.

The research found that the decline in spending on salaries is due to lower average pay, which in turn “is mainly driven by the 12-year decline in the average experience level” in New Orleans.

Buerger noticed another difference between teachers in New Orleans and elsewhere in the state. “These younger teachers [who] have one or two years experience are getting paid more here than they would in other districts in Louisiana,” he said.

But salaries make up just a third of the instructional spending drop. Half of it is due to reduced spending on benefits.

Teachers in traditional public schools participate in the Teachers Retirement System of Louisiana, which provides a set pension after they work a certain number of years.

Schools must make a substantial contribution to the pension plan each year; this year, it’s 25.5 percent of the employee’s salary. These contributions have increased in recent years as the state tries to close a funding gap.

The high price deters many charter schools from participating in the teachers’ pension system, so they offer 403(b) plans, which are similar to 401(k) plans. Employees contribute a certain percentage of their pay, and the school may match a portion. Those teachers have no guaranteed pension; their retirement pay is based on the performance of the investments they choose.

In 2013, a single-site charter estimated it would save $250,000 by pulling out of the state pension system and switching to a 403(b) plan.

Transportation costs up by a third

Buerger and Harris also found that transportation costs have risen 33 percent more than they would have if the school hadn’t become predominantly charters. They said they expected that, given new requirements for busing and a school choice model that did away with neighborhood-based schools.

“You can organize transportation in a centralized way, and when you decentralize, it you lose all economies of scale,” Buerger said.

[module align=”left” width=”half” type=”pull-quote”]Harris said when he talks to charter leaders, they say they like to control their academic calendar and school schedule. “It’s more expensive that way, but they seem to think that’s an important part of allowing them to be distinctive schools,” he said.[/module]

That finding corroborates The Lens’ reporting. In 2013, The Lens surveyed all charter organizations in the city and found that spending and the time students spent on buses had risen with the proliferation of school choice in New Orleans.

Harris said when he talks to charter leaders, they say they like to control their academic calendar and school schedule. This leads them to seek individual bus contracts because it’s hard to coordinate with a charter network that has a different calendar.

“It’s more expensive that way, but they seem to think that’s an important part of allowing them to be distinctive schools,” he said.

That observation also corresponds with our 2013 transportation series. Crocker College Prep’s contract with Hammond’s Transportation cost $1,050 per student. Encore Academy, located in the same building, used Apple Bus Company and paid $785 per student.

Encore’s busing was provided through FirstLine Schools. That year, the Recovery School District also partnered with FirstLine under the Apple contract.

Buerger says there is more research to be done. This study didn’t break out spending differences between charter networks, but he plans to look at that in the future.

“For me as a researcher,” he said, “it’s really exciting to go to the next step and see what kind of variation we have between [charter management organizations] and … single-site schools.”

Read the report

This story was updated after publication to include details about International School of Louisiana’s experience with a vendor to handle its finances. (Jan. 17, 2017)