If you do it for the local, the visitor will come; if you do it for the visitor, you will lose the local and, eventually, lose the visitor as well, because it is the local who gives a place character.

I have written or said this many times in many different places and contexts, but never has it been as true as it is today in New Orleans.

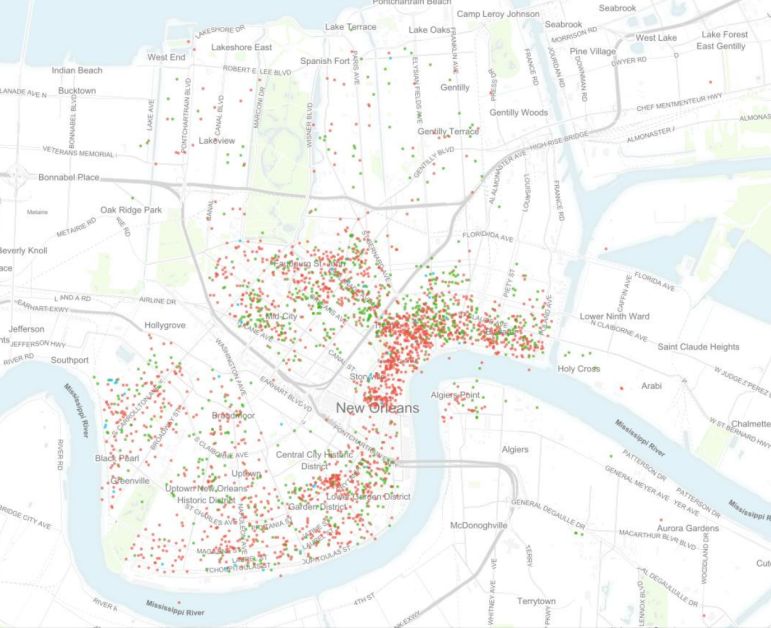

The recent maps of bed-and-breakfast units and other short-term rentals in New Orleans are frightening — frightening, that is, if you care about the heart and soul of this city and not just about lining your pockets with illegitimate gains.

The maps show the short-term rentals, both single rooms and whole households, in all the prime and not-so-prime neighborhoods where longtime residents and recent arrivals have been living, the very people at the heart of this city’s celebrated, but top-sided, recovery. They, not the in-and-out visitor, are the backbone of their neighborhoods and thus of the whole city.

The City Council tries to make us believe that selectively legalizing and “regulating” short-term rentals is the best way to go, especially in light of the so-called tax “windfall” the city will reap.

Let’s first dispel the tax myth. The city gets only 1.5 percent of the 13 percent hotel/motel tax. Nine percent goes to the convention center and related tourist organizations, all of them state authorities. Does anyone believe the state Legislature will share more of those dollars with the city than they do now, given that the state, in the aftermath of the disastrous Jindal years, effectively is broke?

The Council’s proposed regulations also seem to assume that everyone will register for a permit, follow the rules and honestly report taxable earnings.

Second, the proposed regulations are accompanied with promises of “enforcement.” Enforcement? In this city, rules are broken with abandon and impunity — like paving front yards for parking, creating unpermitted curb cuts, and flouting commercial regulations? Enforcement is a joke in New Orleans even without suddenly legalizing and trying to regulate thousands of short-term rentals.

What ruined the Quarter as a community now threatens the whole city.

The bed-and-breakfast phenom — in legal and illegal forms — has been around for decades. Where have the enforcers been hiding? Allegedly, a portion of the new taxes will be devoted to enforcement. But nobody should put faith in that, nor is there any reason to expect the City Council to enact new enforcement rules with any teeth to them.

Just look at the Council’s performance in recent years. It takes even longstanding rules lightly. Some Council members, for example, consider well-established Historic District designations and assorted zoning regulations — actual laws — to be a mere “guide” for their decision making, not the legal framework they were established to be.

Some Council members seem to believe that any new development is good, regardless of scale, zoning or shrinking of the city’s historic fabric, which is what visitors come to see in the first place.

What confidence can we have that they will enforce new regulations? And who will be able to truly tell what is legal or not? State legislation now under consideration would require rental sites to share the information on all rentals and would require payment of the hotel/motel tax. This could be significant, if approved, because enforcement is near impossible without the requisite data.

The proposed rules are so intricate — hinging as they do on rooms per unit, parking available per visitor, units rented per month and per block — that property owners will easily fast-talk their way out of alleged violations or simply camouflage their weekend rentals as longer-term. Owners are required to be licensed and on site for most rentals — but not if the whole household is rented.

Again, will the enforcers be there to check? And where property owners don’t have to live on site, the city will be wide open to speculators buying up properties for the sole purpose of turning them into short-term rentals. Something like this is already evident in the French Quarter and other choice neighborhoods where “ghost condos” are proliferating.

Another Council stipulation is that short-term rentals be limited to two to four per block. That’s a sure way to pit neighbor against neighbor and invite abuse. As envisioned, the regulations would limit each of the four short-term units per block to taking in tenants for a maximum of 30 days a year. Who will be there to enforce the law when time limits are exceeded or additional short-term contracts are signed by owners claiming they didn’t use up their full allotment of days during the four officially sanctioned rentals?

The proposed regs also would allow owners of doubles to live in one half and rent out the other as a full-time B&B — a provision that would essentially turn double-shotgun neighborhoods like Marigny, Bywater and parts of the French Quarter into hotel districts.

It is reasonable to allow people to rent out a room in their homes when they are present. This provision helps owners pay increased taxes, utility bills and water fees. Chances are they will rent responsibly as well, given that they will be on hand to monitor rowdy, slovenly or dangerous behavior. It is also reasonable, as the proposed regs would allow, for an owner to rent out the whole unit for a minimum of a year and with an enforceable limit to two tenants per bedroom. People get relocated for short periods of time, whether for school or work. But there’s no good reason why traditional sublets like these should be limited to four per block.

According to the recent Planning Commission study, 70 percent of the estimated 2,400-4,000 short-term rentals are now for the whole house. Eliminating short-term, whole-house rentals would go a long way toward cooling off an overheated market by making those properties available again to legitimate, longer-term tenants.

Short-term rentals used to be primarily a French Quarter problem. But just as oversized trucks pass through the Quarter with impunity, even when they take out balconies, property owners then and now rent to whomever and how many they choose. This is the pattern spreading to multiple neighborhoods.

City leadership for some time has been happy to look the other way, based on the badly mistaken notion that attracting more and more tourists is a measure of the Quarter’s good health. In fact it has undermined the Quarter’s once-unique character as a mixed-use district that compatibly accommodated both commercial and residential uses.

What ruined the Quarter as a community now threatens the whole city. Short-term rentals are spreading like kudzu, despite their obviously negative impact on the city’s livability.

The strength of this city historically has been the vigor and cohesiveness of its neighborhoods. This was never so apparent as after Katrina; neighborhoods are where the recovery first took root.

Legalizing short-term rentals guarantees big rips in the beautiful patchwork that is New Orleans. Neighbors who once looked after each other now don’t speak, or they look at each other with suspicion. Residents in neighborhoods without driveways find street spaces taken up by visitors. Residents, once rarely disturbed by anything more serious than a curbside musician, are now plagued by comings and goings from boozy bashes in overcrowded weekend rentals — and not just during carnival.

Clearly, residents of the worst-impacted neighborhoods are up in arms and rightly so. The hotel industry also loses big time as short-term rental options proliferate. And what about the city’s wonderful assortment of legal, often charming bed-and-breakfasts? They pay taxes, follow the rules and then see their businesses undermined by unfair competition. This is the absence of anything that could be called a level playing field.

And why are the universities not up in arms? Their out-of-town students depend on reasonable rentals to be able to matriculate here. Add over-the-top rent to already sky-high tuitions and students are likely to go elsewhere.

And where are the banks? Many a property now operating as a short-term rental is described as a single residence on the mortgage papers. Plenty of these owners also have homestead exemptions.

Even before the proliferation of short-term rentals, the city’s cost of living was escalating rapidly, heavily weighted by rising rents and property prices. New Orleans already is the nation’s second worst metro, as measured by the proportion of tenants who pay 50 percent or more of their income for housing.

Renters are being pushed out of their homes and out of the parish, making for longer and longer commutes to daily jobs — long a bane of the low-income workers who can least afford it.

For too long, city leaders have fixed their sights on one economic measure and one alone: attracting more and more tourists. But if the goal is a balanced, desirable city — one tourists will want to visit for decades to come — limits on tourism must be imposed right now. If not, the goose that lays the golden egg will soon be dead or a Disneyfied cartoon sketch of its former self.

Roberta Brandes Gratz is an award-winning journalist whose recent book is “We’re Still Here Ya Bastards: How the People of New Orleans Rebuilt Their City.”