Raising $50 billion for the ambitious Master Plan to rebuild the Louisiana coast was never going to be easy. Though the BP oil spill will yield billions of dollars for projects, the state still could come up $20 billion short. To close the gap, the state will try to change how the Mississippi River is dredged and will consider pollution-credit programs.

I had just one question for Kyle Graham, executive director of the state Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority: How do we pay for the 50-year, $50 billion 2012 Master Plan for the Coast, billed as the last, best chance to prevent much of coastal Louisiana from being swallowed by the Gulf?

Graham laughed. It was a “how much time do you have?” kind of laugh, mixed with “this isn’t simple to explain” exasperation.

It took an hour, and he was right: It isn’t simple. But his answer can be boiled down to these points.

-

That 50-year, $50-billion framework spelled out in the 2012 Master Plan was only a starting point. This effort is meant to be adaptive — not just in terms of science, but funding. So it could end up being longer or shorter, and more or less expensive.

-

To achieve the current plan’s goals, the coastal agency needs to spend $500 million to $1.5 billion on projects each year.

-

The state has only three sources of recurring revenue for the plan, totaling about $280 million annually. Graham’s rough estimate of money from Deepwater Horizon fines and settlements range from $8 billion to $22 billion.

-

When placed against the current building schedule, funding is relatively secure only through the end of this decade. After that, agency leaders hope to raise money through a suite of new sources.

-

If those new sources fall flat, locals will have to foot the bill — and how much they are willing to pay will determine how much coastal wetlands we will have.

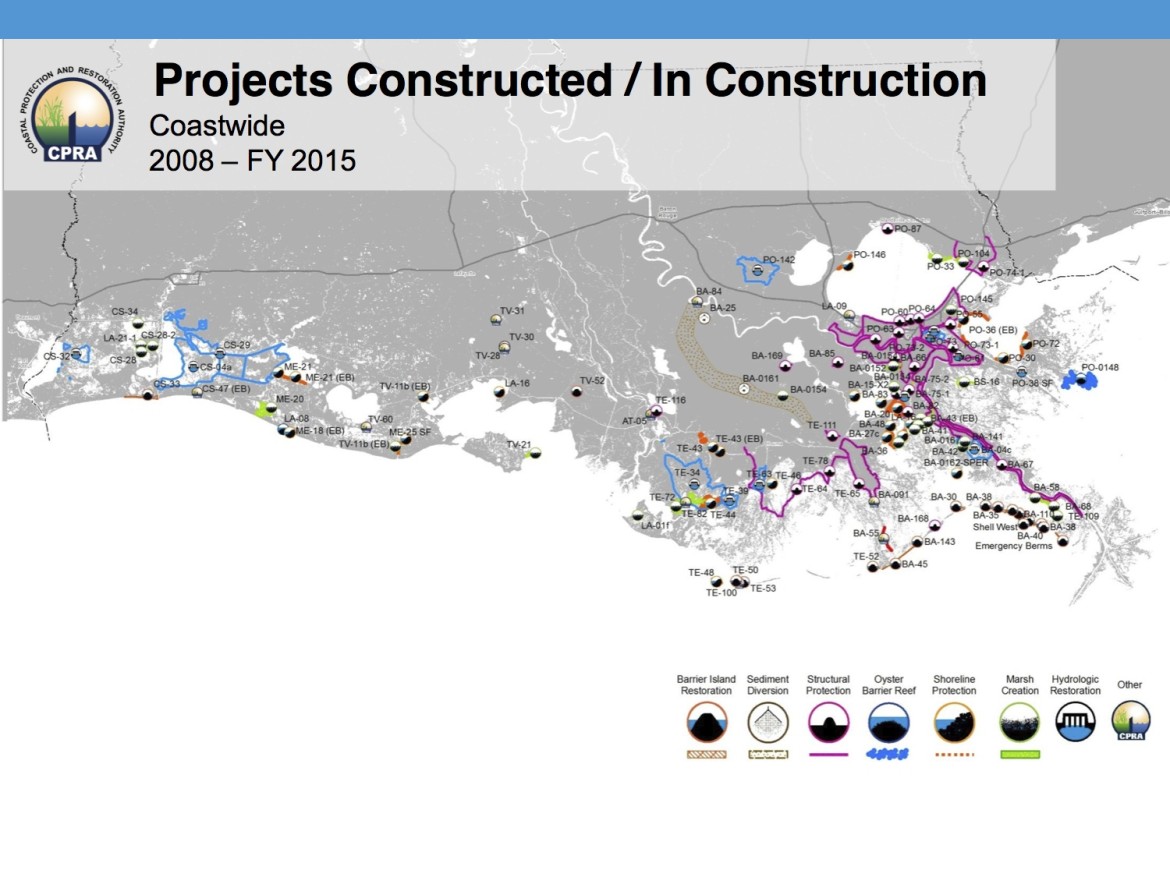

Since 2008, the coastal authority has spent or committed about $2 billion on 76 coastal restoration projects. The agency has put out another $11 billion on 36 structural projects. Most are for flood protection, including the state’s $8 billion share of New Orleans’ $14.5 billion storm surge protection system, which wasn’t part of the 2012 plan.

“There are various sizes of a sustainable coastal Louisiana. And that could depend on how much our people are willing to put up for that.”—Kyle Graham, Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority

But Graham says those figures should not be used as a yardstick for progress toward the final goal.

“We are required to submit a new plan to the Legislature every five years, and what we learn will inform each new plan,” he said. “And it could end up being a $100 billion Master Plan, or a $20 billion Master Plan.”

As Chuck Perrodin, the coastal authority’s chief spokesman, put it, “You don’t fund the Master Plan, you fund Master Plan projects. We don’t go looking for $50 billion, we go searching for funding for projects.”

$50 billionPrice tag for 2012 Master Plan$2 billionSpent on coastal restoration projects so far

The initial plan released in 2007 was largely conceptual, with no spending or time parameters. The 2012 plan is the first to provide that framework.

It includes 109 projects to be implemented in two phases: one from 2012 to 2031 and the other from 2032 to 2061. The authority said if the projects work as its models suggest, Louisiana could start gaining more coastal acres than it loses starting around 2042.

Few sources of reliable, long-term funding

While the authority stresses that plans and funding could change, the public was sold on the 50-year, $50 billion metric.

Finding that $50 billion was always considered a steep challenge for one of the nation’s poorest states. The list of recurring funding streams underlines that challenge:

-

The Coastal Protection and Restoration Trust Fund: $30 million per year from royalties and severance taxes on mineral development.

-

Coastal Wetlands, Planning, Protection and Restoration Act: $75 million to $80 million annually. The money comes from taxes on small-engine fuel and excise taxes on fishing gear. The state must provide a match, which typically comes to $30 million a year.

-

Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act: $170 million annually, starting in 2017. Gulf states will get a portion of federal excise taxes levied on oil and gas production in federal waters. Unexpectedly robust production in the deepwater Gulf means the state will receive its maximum annual allowance of $170 million, Graham said. After 2055 when the cap is lifted, Louisiana’s share could reach $600 million annually.

That comes to about $280 million a year in recurring revenue — and $170 million won’t come until 2017.

Hurricane Katrina, BP oil spill should yield billions more for restoration

But Louisiana’s coastal money search got an early and unexpected boost from two disasters.

As the rest of the nation was struggling through the Great Recession, the massive rebuilding after Hurricane Katrina swelled state coffers. The Legislature sent $790 million of that to the coastal protection agency from 2007 to 2009.

The second windfall came after BP’s Deepwater Horizon drilling rig exploded, sending oil into Louisiana’s wetlands. The companies involved have paid roughly $2 billion for coastal restoration, but more is on the way.

The RESTORE Act will divide BP’s Clean Water Act fines among the five Gulf states according to a formula worked out by Congress. The trial to determine the size of these fines is ongoing; most estimates put Louisiana’s direct share at $3 billion to $5 billion.

$3-5 billionEstimate of BP’s Clean Water Act fines$3-15 billionWhat it could pay under separate environmental law

More BP money will come from the Natural Resource Damage Assessment, a legal process that puts a dollar value on the damage done to the state’s environment, including fish and wildlife.

While Louisiana officials hope for a quick resolution of the lawsuit to determine how much they’ll get from the RESTORE Act, Graham said the state is in no hurry to finish the assessment. That’s because environments exposed to large spills in Alaska and Mexico are suffering long-term damage.

He estimates BP could end up paying $3 billion to $15 billion as the result of the assessment.

“We’re seeing some things that really cause pause in some of the generational effects of the oil spill,” he said. “We’ve seen some of those effects in insects, we have seen them in dolphins, in the lack of oyster production and in some of the shrimp reports.

“Now, all of these things have natural oscillations in their production, and we may have to wait awhile to see if this is a trend or a natural oscillation, but we feel very confident about where the case is heading.”

The potential windfall from Deepwater Horizon comes with a downside as well.

“Everyone knows about it [BP’s fines], so it has made it very difficult for us to go out and try to raise funds,” Graham said. “People see the figures that have been in the press and wonder about our need.”

Three ideas to raise more money for restoration

Even if those settlements are on the high end, the state still would be as much as $20 billion short of the $50 billion benchmark.

So Graham’s agency is looking for new sources of recurring income.

Those include the emerging markets for carbon banking and water quality credits. Wetlands have been shown to filter water pollutants and absorb carbon. Louisiana could be in a position to sell that capability to companies and communities that cannot meet regulatory limits.

Graham said his agency has established a methodology for carbon banking and will be ready if that market ever develops. “And there already are examples of states and counties in Iowa that are using water quality credits in the farming community, as well as in Georgia with developers having to bank water quality credits for actions like paving parking lots,” he said.

[module align=”right” width=”half” type=”pull-quote”]A third initiative would be historic if successful: changing the way the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers conducts its shipping and flood prevention programs on the river so they also benefit restoration.[/module]

“If we get comfortable with the idea that our wetlands can handle the nutrient output of diversions, that could be another source of income.”

A third initiative would be historic if successful: changing the way the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers conducts its shipping and flood prevention programs on the Mississippi River so they also benefit restoration.

The corps spends about $100 million a year to keep shipping lanes open in the lower river, pumping sand and sediment from shoaling areas into the fast-moving current, which carries it to the Gulf. For years the state has pressed the corps to pump the dredged material into adjacent, sinking marshes — a process called “beneficial use.” The corps has said it lacks the congressional authorization and budget to do so.

According to Graham, the state and the corps may have reached an understanding with the Hydrodynamic and Delta Management Study of the lower river, which they started in 2011.

“One of the major purposes of the study is to find out how we can manage the resources in the river to benefit all of its roles — shipping, flood prevention and restoration,” he said. “We want to stop looking at these as different silos. We want to know how we can manage diversions to benefit shipping and flood prevention, and vice versa.

“And the corps is very much on board with that idea, and working with us toward that goal.”

2061Last year of current Master Plan2042When Louisiana could start gaining more land than it loses each year

The state is also looking at using the nation’s environmental regulations to force a change in the corps’ practices.

“Every time the corps does a project on the river, it impacts the basins on either side of it,” Graham said. “The way it dredges the shipping channel, the way it maintains the levees, the revetments on the river. It all has an impact.

“Every one of those projects needs an Environmental Impact Statement,” he said. “I think the last time they filed one was 1985, and there are court cases that imply those have to be done every five years. So it’s definitely time to relook at that to see if there is something there.”

Changing the corps’ practices could save the Master Plan millions.

“If there is mitigation needed for those actions, the mitigation would be done in areas that would be consistent with our Master Plan,” Graham said.

Price tag of restoration will surely rise

Without those new sources of revenue, Graham admits the state would need help from Congress to complete the current, $50 billion plan.

And whatever the price tag is today, inflation will push it higher by the time some projects start.

John Driscoll, a New Orleans-based financial analyst, said the 2012 estimates were done in 2010 dollars, even for projects decades away. When he accounted for 3 percent annual inflation, the cost of the current plan is $113 billion.

And Congress has so far rejected the Obama administration’s requests for Master Plan funding.

While Graham said it’s possible to create a sustainable coastal Louisiana with only local funding, he also acknowledged there would be limits.

“There are various sizes of a sustainable coastal Louisiana,” he said. “And that could depend on how much our people are willing to put up for that.”

Like he said, the plan was always meant to be adaptive.