The Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority is expected to file suit Wednesday against more than 100 oil and gas companies for contributing to the disappearance of Louisiana’s wetlands. The lawsuit argues that decades of drilling, dredging and extracting has destroyed wetlands that once provided a cushion against hurricane storm surge. With the Gulf creeping ever closer, the agency must spend more to protect metro New Orleans.

Update: See below for our live blog of Wednesday’s news conference about the suit.

Over the last seven months, three New Orleans-area law firms spent thousands of hours researching how to do something that many have talked about, but never tried — hold oil and gas companies accountable for increasing the flood risk to the metro area by destroying coastal wetlands.

In the end, the lawyers settled on a centuries-old legal concept. But they know the success of that choice will depend on the science supporting it.

Live chat, 12:30 p.m. Friday: Bob Marshall takes questions about legal, scientific and political issues related to the suit

“If they believe the expert scientific testimony given by our witnesses, then we win the lawsuit,” said Gladstone “Glad” Jones of Jones, Swanson, Huddell and Garrison, which has a successful track record of suing oil companies.

“That’s what this will all come down to – the science.”

The lawsuit, expected to be filed Wednesday by the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-East, alleges that the companies violated their permits when they did not “maintain and restore” the wetlands involved, and that their projects violated the federal River and Harbors Act of 1899 by reducing the effectiveness of federal levees.

But the heart of the case rests on a centuries-old legal principle called “servitude of drainage.” That doctrine stipulates that someone is liable for damages if he does something to increase the flow of water on another’s property. The courts have ruled the properties do not have to be contiguous.

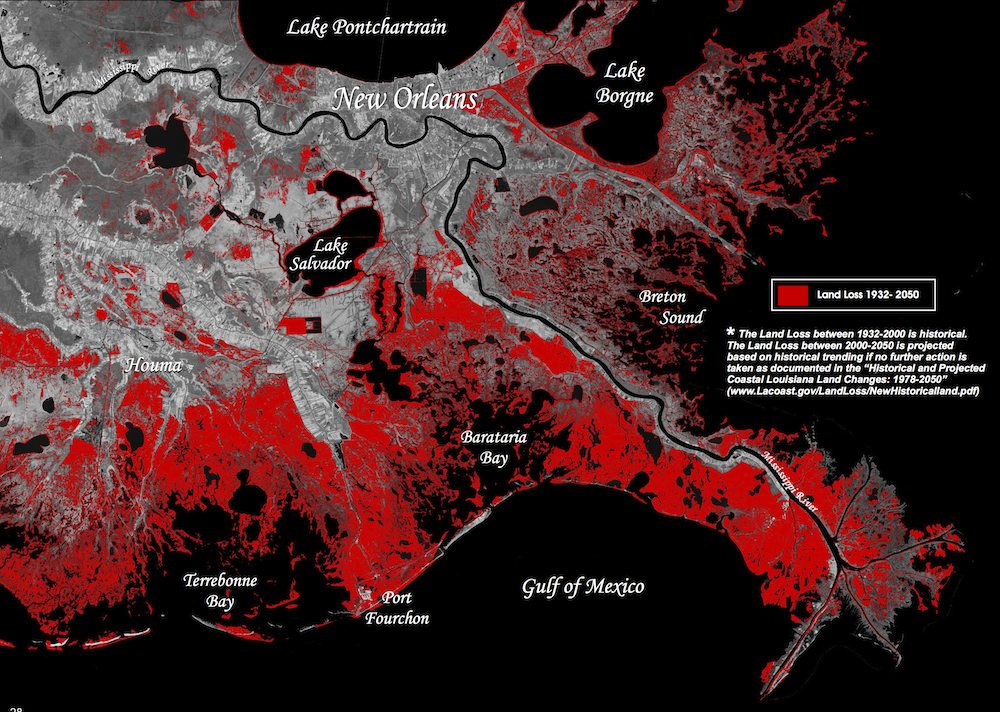

The Flood Protection Authority claims that decades of drilling, dredging and extraction destroyed wetlands that once provided a cushion against hurricane storm surge. With that cushion reduced, storm surge has increased in the parishes under its jurisdiction, leading to a higher risk of flooding.

As a result, the Flood Protection Authority says it has to spend more to protect people and property in the metro area.

The suit asks the companies to repair the damage by bringing the landscape back to its original condition or, if that isn’t possible, to defray the agency’s rising costs.

“No one denies – not even the oil industry – that the canals they dredged helped cause this problem,” said John Barry, vice president of the Flood Protection Authority.

“Now, people will say there are other causes, and we’re not denying that,” he said. “The levees on the river, obviously, are a major cause. But the federal government built those levees, and they’ve been spending billions of dollars on better flood protection and coastal restoration projects in this area.

“What we’re saying to the oil companies is, ‘It’s time for you to step up now for the damage you did.’”

The suit names nearly 100 oil and gas companies as defendants.

Research links canals, coastal erosion

To win its case, the Flood Protection Authority plans to use years of scientific research to prove that the oil industry impacted drainage across its jurisdiction – the metro area east of the Mississippi River.

Plenty of science is available.

For decades, researchers have been documenting the relationship between canal dredging and the state’s loss of almost 2,000 square miles of coastal wetlands. The state Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, using research from the U.S. Geological Survey, says almost 10,000 miles of canals have been dredged for oil and gas. Many researchers believe the figure is considerably higher because the agency’s numbers rely mostly on permits, and there wasn’t a reliable permitting system until passage of the federal Clean Water Act in 1972.

2,000Square miles of coast lost10,000Miles of canals dredged in wetlands

Canals have been singled out as a primary villain of the land loss because their impacts hit several layers of the wetlands ecosystem.

Gene Turner, Louisiana State University’s Distinguished Research Master and Shell Endowed Chair in Oceanography and Wetlands Studies, has been quantifying canal impacts for decades.

“You have the direct loss of marsh caused when you dredge these canals converting wetlands to open water,” said Turner, who has reported that the average oil field canal is 12 feet deep and more than 50 feet wide.

“But then they took the material they dredged to dig the canals and deposited it on the bank, creating a spoil levee about eight to 12 feet high and 15 feet wide or wider. That’s more direct loss.”

Turner said his studies show the direct loss of wetlands from the canals and their spoil banks comes to 16 percent of the 2,000 square miles lost since the 1930s.

However, the indirect impacts of the canals resulted in an even larger area of wetlands being converted to open water, Turner and other researchers have reported. Some of those impacts include:

-

The drowning of entire sections of wetlands when water became trapped between spoil levees

-

Changes in currents that increase bank erosion

-

Disruption of beneficial flooding that could help spread sediments to keep wetlands above sea level

-

Wakes caused by recreational and commercial boats

Turner and other scientists estimate that 35 to 42 percent of the state’s catastrophic land loss could be traced to oil and gas canals. He said a more recent analysis of land loss in the Barataria Basin, soon to be published, places that figure at close to 85 percent.

“Some of the numbers I have place it as high as 90 percent overall,” he said. “But whether it’s 30, 45 or 80 percent, there’s a clear relationship between the number of canals in an area and the amount of land loss. That relationship is undeniable.”

Drilling a factor in subsidence

Canals are not be the only oil and gas industry activity the suit will raise. Research has also shown a direct link between land loss and the extraction of oil and gas from below Louisiana’s wetlands.

Alex Kolker, a researcher and professor at the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium in Cocodrie, La., has published papers showing that subsidence increases, and more wetlands are converted to open water, as oil and gas production in wetlands increases.

“It’s a pretty straight correlation,” Kolker said. “The short version of the story is gas and oil contained in rocks are under pressure, and when you remove those substances, you create a vacuum, which eventually is filled by surrounding materials.”

Land loss well-documented

The Flood Protection Authority will have no trouble using state records to show that thousands of wells have been drilled in its jurisdiction, that those wells pulled millions of gallons of oil and cubic feet of gas from the subsurface, and that companies dredged thousands of miles of canals to reach those spots and move their raw products to collection points and refineries.

The Flood Protection Authority is likely to use published science to prove that those activities contributed to the loss of storm-buffering wetlands in its jurisdiction, which has been significant.

In 2002 the USGS reported that between 1932 and 1990, Plaquemines Parish lost 12 percent of its wetlands, including half of the Bird’s Foot Delta, and St. Bernard Parish lost 17 percent.

The East Orleans Land Bridge, between lakes Pontchartrain and Borgne and key to keeping surge out of lakeside communities in Orleans, St. Tammany, Tangipahoa and the river parishes, lost 17.6 percent of its area.

For years the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and other public agencies have reported that a 1.3-mile wide band of marsh can reduce storm surge by as much as one foot.

So it will be the Flood Protection Authority’s task to prove that the science shows canals and oil and gas production removed those wetlands, changing the drainage in its area, causing higher storm surges to push into the metro area – and forcing it to spend billions to prevent Hurricane Katrina-like disasters from happening.

“We think the science is clear,” said Barry, of the Flood Protection Authority.

If the jury agrees with the science, Jones said, the authority will win its case.

Read the lawsuit

Live blog of news conference

The agency has scheduled a news conference at 10:30 a.m. Wednesday to discuss the lawsuit.